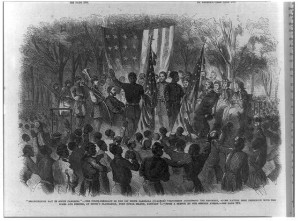

changin’ times: “”Emancipation Day in South Carolina” – the Color-Sergeant of the 1st South Carolina (Colored) addressing the regiment, after having been presented with the Stars and Stripes, at Smith’s plantation, Port Royal, January 1

A man in central New York state was resisting big changes in traditional roles for women and black people in mid-nineteeth century America. He reviewed a presentation by a woman who had spent some time involved with trying to educate and make more self-sufficient contrabands around Beaufort, South Carolina. To the extent that this reviewer was reporting the facts right, it appears that some of the people working to free the slaves were fleecing the ex-slaves.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in January 1864:

Politics in Petticoats.

On Sunday evening last, an Abolitionist of the feminine gender undertook to enlighten the people of Seneca Falls upon the dark subject of the Negro. The meeting was held in the Abolition temple of the Wesleyan Church, and was presided over and encouraged by the clergyman who officiates at the Abolition altar of the Church. A large crowd was on hand, most of whom, probably, like myself, out of curiosity to witness the masculine freaks of a masculine woman, and the better to draw the contrast between a true lady in the quiet sphere of domestic life, and one who perverts the position which Providence originally assigned to her, by mounting a political forum, and haranguing a mixed multitude – male and female.

It appeared by her story that she had been “the General Superintendent,” as she called herself, of eight or nine hundred contrabands, at the negro depot of the Government in South Carolina, and which contrabands had been taken or decoyed away from their former masters by the orders of Abraham Lincoln &Co., and were collected in squads around the once beautiful city of Beaufort and on the islands adjacent. She acknowledged that the negroes were naturally lazy, and that the year 1862 proved a very unprofitable one for Uncle Sam in his negro farming speculation; that the one hundred Yankee Abolition school-teachers who went down there to try to teach the young niggers, were completely discouraged, and all returned home to the North, utterly disgusted with their lovely employment; but that now matters look more encouraging, because the Administration is soon to sell all those beautiful plantations to the darkies at $1, 25 per acre, so that they will have a fine chance to revel among the luxuries of their former refined masters. This she maintains is to be the blessed result of our glorious civil war.

She confessed that she once lived on the southern borders of Ohio, and had assisted slaves to escape from their masters to the North by the underground railroad; that she had recently been engaged in buying goods at the North and selling them to the contrabands “at a profit,” while she was “General Superintendent;” that the poor negroes were shamefully cheated by our officers, soldiers and sutlers, by purchasing of them poultry, eggs, vegetables, &c., and paying for the articles in old labels of Perry Davis’ Pain Killer,” which the officers assured them was a new currency recently issued by Father Abraham. In fact, according to her own confession, the poor, ignorant contrabands are ground between the upper nether mill-stones; for, what she failed to take from them by her trading speculations, was abstracted by others for labels of Davis’ Pain Killer. Truly a beautiful result of antislavery fanaticism!

She specially glorified Lincoln Cabinet for one thing, and that was the rumored fact that “the daughter of Old John Brown is now teaching a school composed of the negroes formerly owned by Gov. Wise.” It will be recollected that Wise was Governor of Virginia when John Brown was tried by law, and justly hung, for his crimes and massacres, unprovokingly committed upon the peaceable citizens of Virginia, and yet this fanatical woman now vauntingly applauds the murderous acts of John Brown, by proposing to honor and compensate his daughter!

The lady, however, uttered some truth when she hinted at the monstrous frauds committed by agents of Lincoln’s administration, and the enormous peculations and stealings at the Custom House in New York and other places, “while 50,000 liberated negroes are starving and freezing to death on the banks of the Mississippi.”

On the whole, she showed conclusively that the Abolitionists were effectually hung upon the horns of a dilemma, for they don’t know any more what to do with the poor blacks, after they are liberated by their hypocritical friends, than did the fellow with the elephant which he drew in a lottery. The meeting behaved very civilly, and only one or two faint efforts at applause were attempted, which didn’t produce the exhilarating effect that was intended, and the crowd dispersed after they had been invited by the clergyman to buy some pictures of the lady, purporting to show some dreadful effects of slavery. It is very evident that Abolition harangues do not draw the sympathy of respectable people now, as they formerly did in the flourishing of Old John Brown and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

**

The Port Royal Experiment “was a program begun during the American Civil War in which former slaves successfully worked on the land abandoned by plantation owners.” The town of Mitchelville was built on the current hilton head Island as a town for escaped slaves and in response to issues involving the black people living in close proximity to Union troops:

Many Union officers complained that the ex-slaves “were becoming a burden and a nuisance.” Some Union troops stole from the ex-slaves, and it is apparent from primary resources that the racial attitudes of some of the Union troops towards the blacks were negative; General Mitchel remarked that he found “a feeling prevailing among the officers and soldiers of prejudice against the blacks.” By February 1862, the ex-slaves were living inside the Union camps, in whitewashed, wooden barrack-like structures built specifically for them and under the control of the Quartermaster’s Department; similar camps were also built in nearby Beaufort, Bay Point, and Otter Island, By October 1862, however, this approach was seen as a failure, with living conditions being considered substandard and the obvious need to separate the soldiers from the ex-slaves and vice-versa …

![[Freedmen's school, Edisto Island, S.C.] (by Samuel A. Cooley, between 1862 and 1865; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-11194)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/11194r-300x184.jpg)