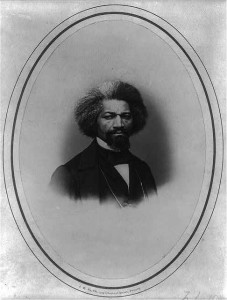

It’s been almost two years since we’ve put up a report on Frederick Douglass speaking at New York City’s Cooper Institute. 150 years ago this week he spoke there again. The war was dragging on, and it had to be a war for the abolition of slavery throughout the country. President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation did not go far enough and “may yet be negatived by Congress, the Supreme Court, or by cannon”, but President Lincoln did treat him with respect at the White House.

From The New-York Times January 14, 1864:

Frederick Douglass on the “Mission of the War.”

Last evening Mr. FREDERICK DOUGLASS addressed a very large and brilliant assemblage in the hall of the Cooper Institute, on the “Mission of the War.” The lecture was in behalf of the Woman’s Loyal League. Mr. WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT who was announced as intending to preside, was called to the bedside of a dying relative, and Mr. OLIVER JOHNSON, Editor of the Anti-Slavery Standard, filled his place. Mr. DOUGLASS, on being introduced, remarked that men on all sides tell us that Slavery is dead; that it expired as the first shot was fired from Sumter. He was not so confident He looked facts sternly in the face, and saw in the future no miraculous abolition of Slavery. This war is a great national opportunity, which may be improved to a national salvation, or neglected to a national ruin. Vain the might of armies, vain the strength of armaments, if the Government fails to observe those principles of justice and liberty at bottom of the controversy. We are in the salutary school of affliction. If it can teach this great nation to respect those great principles toward a long neglected and cruelly crushed race, we are in a fair way for amendment, but, if this teacher is unheeded, whose lessons are burned into us by blood and fire, and thundered in our ears by the roar of a thousand battles, we shall be a warning to other nations to shun our cowardly example. We had seen in 1848 the sublimest revolution the world had yet experienced. It was regarded as the death of kingcraft. In the twinkling of an eye the powers of despotism rallied, and the hopes of democratic liberty were blasted in the moment of their bloom. Grave liabilities may also yet hang over our present struggle against the slave power of this country. The ladies of the Loyal League were to be thanked for keeping the question before the public. We are not yet out of danger. We were once informed by a hitherto sagacious political prophet, that the war would end in ninety days, yet it still rears its head in its third year, alone among rebellions, as a solitary and ghastly horror, never yet conjured among nations, drawing inspiration from a system, haggard, fiendish, and too indecent even to be mentioned in full. It has strewn our land with two hundred thousand graves, and filled it with mere stumps of men, destroyed property beyond the most exaggerated calculation, and piled up a debt heavier than a mountain of gold to be paid by our children; weakened our friends, encouraged our enemies, — and for what? For Slavery — that hell-black enormity that the people of this country have not even yet comprehended. Mr. DOUGLASS, after sketching the origin of the war, observed that this rebellion was enough for the lifetime of any one nation, even should it cover a thousand years, and it should be the voice of every patriot that whether the work cost much or cost little, it should be done thoroughly, [applause,] that it may be the last rebellion ever to curse American soil. The longer the war the better, if need be so, if it succeeds in abolishing the internal system of American Slavery. Say not that this comes from a negro who has no interest in the Union. I feel the deepest sympathy with it. I am an American, [applause,] and with many others participate in the deep privations of the moment. There are vacant places at my hearthstone, once filled by beloved sons, enlisted for the war, whom I live in hopes of seeing return. In this struggle we are writing in the blood of tyrants, the words of eternal justice. The war seems long, but its slow progress is essential to our salvation. The disease, being severe, the remedy must be both powerful and tardy. We were, morally, very low before it commenced, so much so that our great physician. Dr. BUCHANAN, on being called, decided there was no hope for us. We had been literally drugged to death with Pro-Slavery Compromises. There has been nothing so necessary as the slow and steady progress of this war. Why, look how we have grown! (laughing significantly at the enormous audience gathered to hear him, a colored man.) This is not acceptable, evidently, to certain Peace Democrats. The speaker urged the necessity of clearly defining the war as an Abolition war, and not shirking the question, as only in that sense can it be successful. We may admit it to be a war for the Constitution and the Union, but only in the sense that the lesser are included in the greater. Abolition includes both the Constitution and the Union of these States. Slavery was too strong for either. It came to the Constitution and broke it — to the Union, and sundered it. It must now, itself, be crushed. The Democratic party has had no other master than Slavery for forty years. It has made war and peace precisely according to its dictation. The Florida war even was commenced in the cause of Slavery. A few slaves ran from their civilized and religious masters, men of bibles and prayer-books, and took refuge with men of tomahawks. They found more of the milk of human kindness with Seminoles than with their pious and swindling masters.

The speaker, in anathematizing the Democratic party, said there had been noble men in it, but they were outsiders now. It is now a religious party, and says “Blessed are the peacemakers,” and yet, for the sake of stopping the effusion of blood at the South, they arouse it at the North, till it culminates in deeds at which a savage would blush. He said that, notwithstanding our political victories, we are yet in danger of being ground beneath the heel of Slavery, and should consent to no peace which is not an Abolition peace, which declares free the whole colored race — [applause] — and which gives the freedmen of the South every civil and political right with their white brethren — [applause] — including the right to vote. [Great applause.] The dregs of the old treason will yet linger after the war, and the Federal Government needs a friend in the black man to stifle that treason. To win his friendship he must be granted rights. A morning paper says we are requested thus to introduce ignorance and degradation into the body politic. I scout this charge, said the speaker, with scorn. If a negro knows enough to be hanged, he knows enough to vote; if he knows honesty from roguery, he knows enough to vote; if he knows enough to fight for his country, if he knows as much sober as an Irishman when drunk, he knows enough to vote. [Tumultuous cheering,] He had hoped that Slavery and rebellion would find a common grave without further discussion, but found that the Proclamation settled nothing permanently. It may yet be negatived by Congress, the Supreme Court, or by cannon. He detested its principles. It says to rebels, we will take your slaves, but to loyal men, you may keep yours. It should have stricken Slavery everywhere. The President was brought to it with reluctance, as may be found in his letter to Mr. GREELEY. I have been to see the President — a man in a low condition, meeting a high one. Not Greek meeting Greek, exactly, but rallsplitter meeting nigger. Perhaps you would like to know how I, [???] negro, was received at the White House by the President of the United States. Why, precisely as one gentleman would be received by another. [Applause.] He extended me a cordial hand, not too warm or too cold. I had previously in a speech attacked him for his hardiness and vacillation. Without alluding especially to this speech, he defended himself against the charge of vacillation. “Mr. DOUGLASS, (‘he addressed me as Mr. DOUGLASS,’ added the speaker laughingly,) when I take a position, I think no man can say I retreat from it.” Like the rest of us, however, he has often been restrained by policy from doing what he felt to be a virtue; and that should be done.

Mr. DOUGLASS observed that neither the Government or the loyal people have accepted the true mission of this war. We should have felt that the rebellion, was the signal for the entire abolition of Slavery, not simply for the preservation of the Constitution and the Union. We shall never again see the old Union. Its canonized bones sleep beneath the walls of Sumter. We are fighting now for something far beyond the Union in value — national unity, out of which only can Union truly spring. Union is else a body without a soul, a marriage without love, a barrel without hoops, that drops at the first touch. Mr. CALHOUN felt a national unity to be necessary, but strove to base it upon Slavery. Failing in this, his successors have endeavored to cut loose from the North, with broad blades and bloody hands. We want a country that will not brand our noble Declaration of Independence as a [???]. We wish to stay the taunts of Britain and the rest of Europe, and no longer hang our heads in shame, for our boasted liberty upon which Slavery still hangs as a millstone. We want a country where the Methodists from each section can meet in prayer and convention, without pistols and bowie knives, and in which the title of American citizen shall be as comprehensive as that of a Roman citizen in the palmiest days of the empire; where the school-house of New-England shall replace the whipping post of Carolina, and where the merchant shall no longer sell his soul to sell his goods. No North, no South, no East, no West! No white, no black, before the bar of justice.

The speaker took occasion to apostrophise Ireland, as “glorious old Ireland, that respects the black man on her own soil, and only oppresses him when upon Yankee soil.” Much as he deprecated their evil influence in our politics, he could not forget that while a slave, it was an Irishman that advised him to “cut and run,” and that he was once warmly received in Ireland, and welcomed to the platform of Conciliation Hall, by the noble O’CONNELL himself. The Irish have been befooled into the idea that work given to blacks will be taken from them, and that in case of emancipation there would be a rush of freedmen to the North to compete with them in labor. A great mistake. The rush Southward of blacks will be so great that there will not be enough left to save them.

Mr. DOUGLASS, after the lecture, was presented with $100 for his services, but handsomely returned $50 as a donation to the League.

![Prominent candidates for the Democratic nomination at Charleston, S.C. [Composite of bust portraits of Stephens, Orr, Davis, Guthrie, Slidell, Pierce, J. Lane, Hunter, Breckenridge, Douglas, and Houston] (1860; LOC: LC-USZ62-79475)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/3b26522r-300x221.jpg)