This is the first review I saw of November 19th’s Gettysburg cemetery dedication in the Richmond Dispatch. It focused on Lincoln’s and Seward’s responses to serenaders the evening before and the main speech by Edward Everett on the 19th.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch November 25, 1863:

The Gettysburg cemetery Celebration — the speeches.

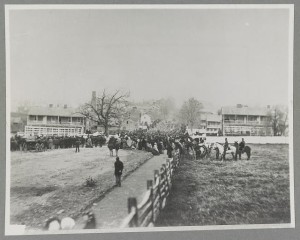

The Gettysburg cemetery dedication was entirely Yankeeish. The Star Spangled Banner was all over the ground, but was adorned with some strings of black in view of the occasion.–The soldiers, citizens, and music were on hand in large quantities. The cemetery contains one corner dedicated to Virginia, which contains two bodies which saw the light first, very likely, in Holland. The day before the dedication Lincoln arrived, and was called out for a speech, and gave forth the following dignified address:

“I appear before you, fellow citizens, merely to thank you for this compliment. The inference is a very fair one that you would hear me for a little while, at least, were I to commence to make a speech. I do not appear before you for the purpose of doing so, and for several very substantial reasons. The most substantial of these is that I have no speech to make [laughter]. It is some what important in my position that one should not say any foolish things if he can help it, and it very often happens that the only way to help it is to say nothing at all. [Renewed laughter.]

“Believing that is my precise position this evening, I must beg of you to excuse me from saying ‘one word.'”

Seward was also serenaded, and made a speech, in which he announced that he was “sixty years old and upwards,” and that forty years ago he fore saw, “opening before this people, a graveyard that was to be filled with brothers failing in mutual political combat.” Attending to his hope that this would be the last “fraternal” war on this continent, old Peckeniff [Pecksniff] gave the following picture of the expected subjugation of the South:

“Then we shall know that we are not enemies but that we are friends and brothers. Then we shall know that this Union is a reality, and we shall mourn, I am sure, with sincerity, equally over the grave of the misguided, whom we have consigned to his last resting place, with pity for his error and with the same heartfelt grief with which we mourn over his brothers, by whose hand, raised in defence of his Government, that misguided brother perished.”

The big gun of the occasion, of course, was the Hon. Edward Everett, of “Boasting,” that secondary and most disgusting edition and representative of the Pilgrim Fathers. After giving three columns to the battle of Gettysburg, he mentioned the question of “State Rights,” which caused that battle, in very few words, and begged his hearers pardon for noticing “this wretched absurdity.” About the present feeling in the South this man said:

“I do not believe there has been a day since the election of President Lincoln when, if an ordinance of secession could have been fairly submitted to the mass of the people, in any single Southern State a majority of ballots would have been given in its favor. No, not in South Carolina. It is not possible that the majority of the people, even of that State, if permitted, without fear or favor, to give a ballot on the question, would have abandoned a leader like Pettigrew, and all the memories of the Gadsdens, the Rutledge, and the Colesworth Pinckneys of the revolutionary and constitutional age, to follow the agitators of the present day.”

With the stiff corpses of one thousand two hundred and eight eighty men lying in a semi-circle around him, killed dead on the field for the express purpose of giving the lie to all such statements, this Massachusetts Yankee stood on the platform at Gettysburg and read aloud this printed folly. He follows it by a little truth, however which we credit to his account:

“In the next place, if there are any present who believe that, in addition to the effect of the military operations of the war, the confiscation acts and emancipation proclamations have embittered the rebels beyond the possibility of reconciliation, I would request them to reflect that the tone of the rebel leaders and rebel press was just as bitter in the first months of the war, nay before a gun was fired, as it is now. There were speeches made in Congress, in the very last session before the rebellion, so ferocious as to show that their authors were under the influence of a real frenzy. At the present day, if there is any discrimination made by the Confederate press in the affected scorn, hatred and contumely with which every shade of opinion and sentiment in the loyal States is treated, the bitterest contempt is bestowed upon those at the North who still speak the language of compromise, and who condemn those measures of the Administration which are alleged to have rendered the return of peace hopeless.”

Exactly. The hatred and contempt for the North has not in three years abated one jot or tittle, nor will it in three hundred. There are refugees and exiles from the frontier who have not had a home for three long years, and who have suffered untold privations, and who to-day couldn’t buy a good sized pocket-handkerchief with all the money they have in the world, and yet these men have not abated a shade in their hatred — that is the word — for the North. Everett thinks the old flag and Butler are very desirable to the South:

“The weary masses of the people are yearning to see the dear old flag floating again upon the Capitols, and they sigh for the return of the peace, prosperity, and happiness, which they enjoyed under a Government whose power was felt only in its blessings.”

He forgets the “weary masses” of the North who are having daily strikes for wages that they may get food, the soldiers’ wives and sewing girls in New York who, at a meeting there a few days since, said they were not getting enough to eat, and the political prisoners in the Yankee bastilles who are pining away under a Government whose power is “felt only in its blessings.”

Seth Pecksniff is a character in Charles Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit. Pecksniff “believes that he is a highly moral individual who loves his fellow man, but mistreats his students and passes off their designs as his own for profit.”

The Lincoln portrait is from U.S. History Images