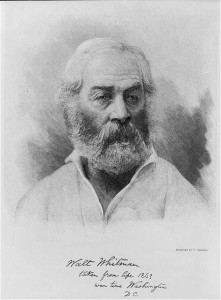

Yesterday while I was doing a little exploring at the Library of Congress, I discovered the image to the left of Walt Whitman, said to be “taken from life” in 1863 (apparently by Alexander Gardner). I read a few of his poems in school, so I wondered what he was doing and thinking during the war.

When he heard that his brother George was wounded at Fredericksburg, Walt traveled south to visit him. George’s wound was superficial, but the sight of the wounded and piles of amputated limbs made a big impression on Walt, who decided to live in Washington, D.C. He got a part-time government job that gave him the time to “volunteer as a nurse in the army hospitals”. A collection of Whitman’s letters, The Wound Dresser contains a letter Walt wrote to his friend Mrs. Abby Price 150 years ago today (pages 128-129). Walt expressed his great affection for the wounded soldiers and his full belief in President Lincoln:

October 15. Well, Abby, I guess I send you letter enough. I ought to have finished and sent off the letter last Sunday, when it was written. I have been pretty busy. We are having new arrivals of wounded and sick now all the time—some very bad cases. Abby, should you come across any one who feels to help contribute to the men through me, write me. (I may then send word some purchases I should find acceptable for the men). But this only if it happens to come in that you know or meet any one, perfectly convenient. Abby, I have found some good friends here, a few, but true as steel—W. D. O’Connor and wife above all. He is a clerk in the Treasury—she is a Yankee girl. Then C. W. Eldridge in Paymaster’s Department. He is a Boston boy, too—their friendship has been unswerving.

In the hospitals, among these American young men, I could not describe to you what mutual attachments, and how passing deep and tender these boys. Some have died, but the love for them lives as long as I draw breath. These soldiers know how to love too, when once they have the right person and the right love offered them. It is wonderful. You see I am running off into the clouds, but this is my element. Abby, I am writing this note this afternoon in Major H’s office—he is away sick—I am here a good deal of the time alone. It is a dark rainy afternoon—we don’t know what is going on down in front, whether Meade is getting the worst of it or not—(but the result of the big elections cheers us). I believe fully in Lincoln—few know the rocks and quicksands he has to steer through. I enclose you a note Mrs. O’C. handed me to send you—written, I suppose, upon impulse. She is a noble Massachusetts woman, is not very rugged in health—I am there very much—her husband and I are great friends too. Well, I will close—the rain is pouring, the sky leaden, it is between 2 and 3. I am going to get some dinner, and then to the hospital. Good-bye, dear friends, and I send my love to all.

Walt Whitman.

In a letter to Abby on October 11, 1863 he mentions a letter to The New-York Times published on October 4th. It is a very long letter that describes Washington, in particular the Capitol Dome and the Statue of Freedom that was being prepared to set atop the dome. Whitman also described the constant travel of army wagons and ambulances through the city streets. Towards the end he predicted that Washington would not long be the U.S. capital because of the national expansion westward, but that it could stand as a vital city in its own right. Here’s a few excerpts.

From The New-York Times October 4, 1863:

LETTER FROM WASHINGTON.; Our National City, after all, has Some Big Points of Its Own Its Suggestiveness Today The Figure of Liberty Over the Capitol Scenes, both Fixed and Panoramic A Thought on Our Future Capital. THE DOME AND THE GENIUS. ARMY WAGONS AND AMBULANCES. FIRST-CLASS DAYLIGHT. OUR COUNTRY’S PERMANENT CAPITAL. A SUNSET VIEW OF THE CITY.

WASHINGTON, Thursday, Oct. 1, 1863.

It is doubtful whether justice has been done to Washington, D.C.; or rather, I should say, it is certain there are layers of originality, attraction, and even local grandeur and beauty here, quite unwritten, and even to the inhabitants unsuspected and unknown. Some are in the spot, soil, air and the magnificent amplitude of the laying out of the City. I continually enjoy these streets, planned on such a generous scale, stretching far, without stop or turn, giving the eye vistas. I feel freer, larger in them. Not the squeezed limits of Boston, New-York, or even Philadelphia; but royal plenty and nature’s own bounty — American, prairie-like. It is worth writing a book about, this point alone. I often find it silently, curiously making up to me the absence of the ocean tumult of humanity I always enjoyed in New-York. Here, too, is largeness, in another more impalpable form; and I never walk Washington, day or night, without feeling its satisfaction. …

But where am I running to? I meant to make a few observations of Washington on the surface.

We are soon to see a thing accomplished here which I have often exercised my mind about, namely, the putting of the Genius of America away up there on the top of the dome of the Capitol. A few days ago, poking about there, eastern side, I found the Genius, all dismembered, scattered on the ground, by the basement front — I suppose preparatory to being hoisted. This, however, cannot be done forthwith, as I know that an immense pedestal surmounting the dome, has yet to be finished — about eighty feet high — on which the Genius is to stand, (with her back to the city.)

But I must say something about the dome. All the great effects of the Capitol reside in it. The effects of the Capitol are worth study, frequent and varied; I find they grow upon one. I shall always identify Washington with that huge and delicate towering bulge of pure white, where it emerges calm and lofty from the hill, out of a dense mass of trees. There is no place in the city, or for miles and miles off, or down or up the river, but what you see this tiara-like dome quietly rising out of the foliage; (one of the effects of first-class architecture is its serenity, its aplomb.) …

The dome I praise, with the aforesaid Genius, (when she gets up, which she probably will by the time next Congress meets,) will then aspire about three hundred feet above the surface. And then, remember that our National House is set upon a hill. I have stood over on the Virginia hills, west of the Potomac, or on the Maryland hills, east, and viewed the structure from all positions and distances; but I find myself, after all, very fond of getting somewhere near, somewhere within fifty or a hundred rods, and gazing long and long at the dome rising out of the mass of green umbrage, as aforementioned. …

Of our Genius of America, a sort of compound of handsome Choctaw squaw with the well-known Liberty of Rome, (and the French revolution,) and a touch perhaps of Athenian Pallas, (but very faint,) it is to be further described as an extensive female, cast in bronze, with much drapery, especially ruffles, and a face of goodnatured indolent expression, surmounted by a high cap with more ruffles. The Genius has for a year or two past been standing in the mud, west of the Capitol; I saw her there all Winter, looking very harmless and innocent, although holding a huge sword. For pictorial representation of the Genius, see any five-dollar United States greenback; for there she is at the left hand. But the artist has made her twenty times brighter in expression, &c., than the bronze Genius is.

I have curiosity to know the effect of this figure crowning the dome. The pieces, as I have said, are at present all separated, ready to be hoisted to their place. On the Capitol generally, much work remains to be done. I nearly forgot to say that I have grown so used to the sight, over the Capitol, of a certain huge derrick which has long surmounted the dome, swinging its huge one-arm now south, now north, &c., that I believe I shall have a sneaking sorrow when they remove it and substitute the Genius. (I would not dare to say that there is something about this powerful, simple and obedient piece of machinery, so modern, so significant in many respects of our constructive nation and age, and even so poetical, that I have even balanced in my mind, how it would do to leave the rude and mighty derrick atop o’ the Capitol there, as fitter emblem, may be, than Choctaw girl and Pallas.)

Washington may be described as the city of army wagons also. These are on the go at all times, in all streets, and everywhere around here for many a mile. You see long trains of thirty, fifty, a hundred, and even two hundred. It seems as if they never would come to an end. The main thing is the transportation of food, forage, &c. Then ambulances for wounded and sick, nearly as numerous. Then other varieties; there will be a procession of wagons, bright-painted and white-topped, marked “Signal Train,” each with a specific number, and over all a Captain or Director on horseback overseeing. When a train comes to a bad spot in the road this Captain reins in his horse and stands there till they all get safely by. If there is some laggard left behind, he will turn and gallop back to see what the matter is. He has a good riding horse, and you see him flying around busy enough.

Then there are the ambulances. These, indeed, are always going. Sometimes from the river, coming up through Seventh-street, you see a long, long string of them, slowly wending, each vehicle filled with sick or wounded soldiers, just brought up from the front from the region once down toward Falmouth, now out toward Warrenton. Again, from a boat that has just arrived, a load of our paroled men from the Southern prisons, via Fortress Monroe. Many of these will be fearfully sick and ghastly from their treatment at Richmond, &c. Hundreds, though originally young and strong men, never recuperate again from their experience in these Southern prisons.

The ambulances are, of course, the most melancholy part of the army-wagon panorama that one sees everywhere here. You mark the forms huddled on the bottom of these wagons; you mark yellow and emaciated faces. Some are supporting others. I constantly see instances of tenderness in this way from the wounded to those worse wounded. …

Walt Whitman also wrote some war poetry. For example, “Beat! Beat! Drums!” was published in the September 28, 1861 issue of Harper’s Weekly (at Son of the South).

The image of President Lincoln is from U.S. History Images