From The New-York Times October 6, 1863:

Lee’s Report.

The specific object of LEE’s Summer invasion of Pennsylvania was a matter of profound mystery and endless speculation at the time; and the mystery is not perfectly cleared up by his official report of that campaign, which has just seen the light at Richmond, and which we give in full this morning. It was thought by some that the gigantic army of the rebels, whose numbers were accurately stated by a reliable City co[n]temporary at 190,375, meant nothing less than the capture of Washington and Baltimore, the capture of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, the capture of New-York and Boston, and, for that matter, the capture of Cincinnati and Rouse’s Point. With Panic preceding them, Death accompanying them, and Desolation following in their wake, there seemed no reason why they should not work their will and wreak their vengeance upon the North; and those who remember the history of that time will recall how the Tribune proposed to placate them in advance, and to “bow to destiny,” as impersonated in JEFF. DAVIS, in event of their “watering their horses in the Delaware.”

Gen. LEE, in the course of his report, sets forth several insufficient and incoherent reasons for his undertaking the offensive campaign of June and July. He judiciously says not a word about Washington, Philadelphia, or Baltimore; he indicates no intelligible or comprehensive scheme of operations — no object likely to be successful or decisive, or to compensate for the labors and risks he was about to assume. But he apprises us that as HOOKER’s position opposite Fredericksburgh was unassailable, it was determined to draw him from it — the execution of which purpose embraced the relief of the Shenandoah Valley, and, if practicable, the transfer of hostilities north of the Potomac; and he further thought that he might obtain an opportunity to strike a blow at HOOKER’s army, or at least compel it to leave Virginia, and so break up our plan of campaign for the Summer. In addition to this, it was hoped that “other valuable results” might be obtained. What the other hoped-for results may have been, is left to be surmised; but so far as LEE’s purpose is propounded in the ends given above, we do not think that military men who are now acquainted with the situation as it existed on both sides, will have much occasion to admire the wisdom displayed in his plan or rather his mode of operations. After these preliminary statements, Gen. LEE proceeds to give a view of the movements of each of the three corps of his army, from the line of the Rappahannock and the Rapidan across the Blue Ridge, up the Shenandoah Valley and over the Potomac; but the only thing we find indicating in any way an object or purpose beyond those mentioned, is the statement that after the whole of his army had crossed the Potomac, “preparations were made to advance upon Harrisburgh.” This purpose, however, was frustrated by the northward advance of our army as far as South Mountain, which menaced LEE’s communications with the Potomac, prevented the progress of his march, compelled the concentration of his army on the east side of the mountains, and brought about, at Gettysburgh, that “fair opportunity to strike a blow” at our army which he claims to have sought, but whose result was so different from his anticipations that it compelled him to abandon all his projects, whatever they may have been, retrace his steps to the Potomac, down the Shenandoah Valley, over the Blue Ridge Mountains, and back to the Rappahannock, from which he had set out with such high hopes fifty days before.

This report of LEE confirms the opinion universally entertained, that a grand opportunity was missed to strike a blow at his army while it was at Williamsport, making preparations to retreat across the Potomac. He confesses to his embarrassments in that position, and brings to our knowledge some whose existence we had surmised, but of which we previously had no proof. At the same time, his campaign is throughout tacitly confessed to have been a total and stupendous failure — even accepting his own confession of its objects; but we are persuaded now, as during the pendency of the campaign, that its real and final object was the capture of Washington.

Apparently, the “reliable City co[n]temporary” wasn’t so reliable. Lee’s army numbered about 75,000 during the Gettysburg Campaign. Northern journalists might have found Lee’s campaign unwise; 150 years ago today a Richmond editorial called Union generals cowards, who were already dead and putrefying – above ground. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch October 6, 1863:

The Federal Generals.

–It has been observed that not many Federal Generals have been killed in this war. The military expediency of keeping out of danger is fully appreciated by those heroes, so self-denying of glory, so generous in their distribution of the posts of honor and peril to the humble privates in their ranks. Burnside, butting the heads of his rank and file against the ramparts of Fredericksburg, and ensconcing himself in a snug covert three miles from the roar of battle, is a fair specimen of the military discretion of the Commander in Chief of the Federal forces. It is a rare thing to hear of one of them who is unmindful of the great law of self preservation. Such slaughter as has been witnessed among the common soldiers of the Yankee army has not often been witnessed, nor such exemption from peril as their leaders have enjoyed. Scott, McClellan, McDowell, Buell, Pope, Burnside, Hooker, all live, and have not even a scar to testify that they have ever been engaged in a battle of this war.

And yet, though successful in escaping Confederate bullets, they are as dead, to all intents and purposes, as if they had shared the fate of the thousands whom they have driven to the slaughter. Not one of the long array we have mentioned has survived the fields of their former notoriety. Each and all of them have been paralyzed by the shock of arms which they so carefully kept out of, and laid up in a mausoleum where they are scarcely objects of curiosity to the living world. The Confederates have killed them one and all as effectually as if they had perforated their carcases with Minnie bullets. Better would it have been for their reputation to have perished in the smoke and din of battle than to go down to posterity not only defeated, but disgraced. They have purchased a few years of life at the expense of all that makes life desirable to a soldier. With them the process of decomposition has begun before death, and they are masses of living putrefaction — a stench in the nostrils of all mankind and of themselves.

Our people, therefore, need feel no discouragement if the loss of the enemy in Generals is so much less apparently than our own. In reality, it is greater. Every defeat disgraces them, drives them from their positions, and render them as impotent, and far more contemptible, than if they had been slain in battle.

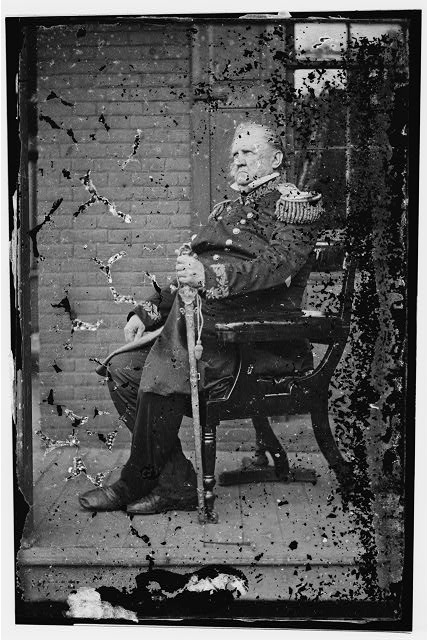

Winfield Scott leading troops into battle? in 1861?

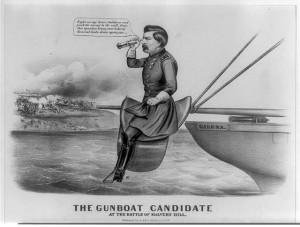

The McClellan cartoon was published during the 1864 presidential campaign.

![Robert E. Lee at Chancellorsville [on horseback, being cheered by troops], May 2, 1863 (c1900; LOC: LC-USZ62-51832)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/3a51856r-235x300.jpg)