It might not be a coincidence that that the same issue of the Richmond Daily Dispatch that praised the Confederate armies also published a letter written by George Washington that expressed his concern with the seeming apathy of Americans not in his army. He seems to be urging Congress to take some action to correct inflation and currency depreciation. Civilians and presumably Congressmen are ignoring the plight of the army as they enjoy their three hundred pound concerts. Meanwhile, “a great part of the officers of the army, from absolute necessity, are quitting the service; and the more virtuous few, rather than do this, are sinking by sure degrees into beggary and want.”

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch September 4, 1863:

The Darkest hour of the Revolution.

The following is a letter written by George Washington to Col. Benjamin Harrison, of Va. It contains matter which merits the deepest and most serious reflection at this time:

Philadelphia, Dec.30, 1778.

To Benjamin Harrison:

Dear Sir:

I have seen nothing since I came here, on the 22d inst., to change my opinion of men or measures, but abundant reasons to be convinced that our affairs are in a more distressed, ruinous, and deplorable condition than they have been since the commencement of the war. By a faithful laborer in the cause, by a man, who is daily expending his private estate, for not even the smallest advantages not common to all in case of a favorable issue to the dispute; by one who wishes the prosperity of America most devotedly, but sees it, or thinks he sees it, on the brink of ruin, you are be sought most earnestly, my dear Col. Harrison, to exert yourself in endeavoring to rescue your country by sending your best and ablest men to Congress. These characters must not slumber nor sleep at home in such a time of pressing danger. They must not content themselves with the enjoyment of places of honor or profit in their own State, while the common interests of America are mouldering and sinking in irreparable ruins, if a remedy is not soon applied, and in which these also must ultimately be involved.

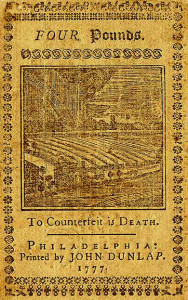

If I could be called upon to draw a picture of the times and of men, from what I have seen, heard, and in part know, I should, in one word, say, that idleness, dissipation and extravagance seem to have laid fast hold of most of them; that speculation, peculation, and an insatiable thirst for riches, seem to have got the better of every other consideration, and almost of every order of men; that party disputes and personal quarrels on the great business of the day, while the momentous concerns of an empire, a great and accumulating debt, ruined finances, depreciated money and want of credit, which, in its consequences, is the want of everything, are but secondary considerations, and postponed from day to day and week to week, as if our affairs wore the most promising aspect. After drawing the picture, which from my soul I believe to be a true one, I need not now repeat to you that I am alarmed, and wish to see my countrymen aroused. I have no resentments, nor do I mean to point at particular characters. This I can declare to you, upon honor, for I have every attention paid to me by Congress that I can possibly expect, and I have reason to think that I stand well in their estimation. But in the present situation of things, I cannot help asking where are Mason, Wythe, Jefferson, Nicholas, Pendleton, Nelson, and another I could name? And why, if you are sufficiently impressed with your danger, do you not, as New York has done in the case of Mr. Jay, send an extra member or two for at least a certain limited time, till the great business of the nation is put upon a more respectable and happy establishment? Our money is now sinking fifty per cent. a day in this city, and I shall not be surprised in the course of a few months if a total stop is put to the currency of it; and yet an assembly, a concert, a dinner, or supper that will cost three or four hundred pounds will not only take men off from acting, but even from thinking of it, while a great part of the officers of the army, from absolute necessity, are quitting the service; and the more virtuous few, rather than do this, are sinking by sure degrees into beggary and want. I again repeat to you this is not an exaggerated account. That it is an alarming one I do not deny; and I confess to you that I feel more real distress on account of the present appearance of things than I have at any one time since the commencement of the dispute. But it is time to bid you adieu. Providence has heretofore taken us up when all other means and hopes seemed to be departing from us.

I am yours, &c.,

George Washington.

General Washington might be implying that his recipient should think about getting up to Philadelphia to help Congress. Virginian Benjamin Harrison (1726-1791) was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and served in the Continental Congresses, where he was nicknamed “Falstaff of Congress.” He left Congress in 1777 and in 1778 was chosen as Speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses. His son and great-grandson became U.S. presidents.