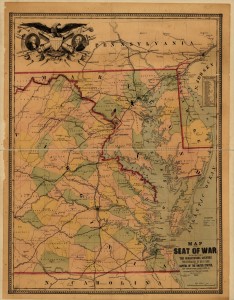

150 years ago today folks in Richmond could read about the ingenuity and daring of some Confederate prisoners of war who escaped from Fort Delaware and/or the recently built barracks on Pea Patch Island.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch August 28, 1863:

Escape of prisoners from Fort Delaware.

–Yesterday afternoon five Confederate prisoners: A. L. Brooks and C. J. Fuller, company G, 9th Georgia; J. Marian, company D, 9th Ga.; Wm. E. Glassey, co B, 18th Miss., and Jno, Dorsey, co. A, Stuart’s Horse Artillery, arrived here from Fort Delaware, having made their escape from Fort Delaware on the night of the 12th inst. The narrative of their escape is interesting. Having formed the plan to escape, they improvised life preservers by tying four canteens, well corked, around the body of each man, and on the night of the 12th inst. proceeded to leave the island. The night being dark they got into the water and swam off from the back of the island for the shore. Three of them swam four miles, and landed about two miles below Delaware City; the other two, being swept down the river, floated down sixteen miles, and landed at Christine Creek. Another soldier (a Philadelphian) started with them, but was drowned a short distance from the shore. He said he was not coming back to the Confederacy, but was going to Philadelphia. He had eight canteens around his body, but was not an expert swimmer.

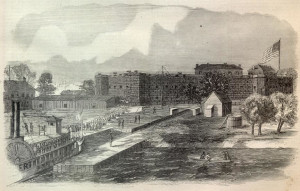

THE ARRIVAL OF TWO THOUSAND VICKSBURG PRISONERS AT FORT DELAWARE.—[SKETCHED BY MR. D. AULD, FORTY-THIRD OHIO.]

The three who landed near Delaware City laid in a cornfield all night, and the next evening, about dark, started on their way South, after first having made known their condition to a farmer, who gave them a good supper. They travelled that night twelve miles through Kent county, Del., and the next day lay concealed in a gentleman’s barn. From there they went to Kent county, Md., where the citizens gave them new clothes and money. After this their detection was less probable, as they had been wearing their uniforms the two days previous. They took the cars on the Philadelphia and Baltimore Railroad at Town send and rode to Dover, the capital of Delaware. Sitting near them in the cars were a Yankee Colonel and Captain, and the provost guard passed through frequently. They were not discovered, however, though to escape detection seemed almost impossible. They got off the train at Delamar and went by way of Barren Creek Springs and Quantico, Md., to the Nanticoke river, and got into a canal.

Here they parted company with five others who had escaped from Fort Delaware some days previous, as the canoe would not hold ten of them. In the canoe they went to Tangier’s Sound, and, crossing the Chesapeake, landed in Northumberland county, below Point Lookout, a point at which the Yankees are building a fort for the confinement of prisoners. They met with great kindness from citizens of Heathsville, who contributed $120 to aid them on their route. They soon met with our pickets, and came to this city on the York River Railroad. These escaped prisoners express in the liveliest terms their gratitude to the people of Maryland and Delaware, who did everything they could to aid them. There was no difficulty experienced in either State in finding generous people of Southern sympathies, who would give them both money and clothing, and put themselves to any trouble to help them on their journey.

These gentlemen state that a large number of our prisoners at Fort Delaware have taken the [o]ath and enlisted in the Yankee service. The Yankees have already, from prisoners who have taken the oath, enlisted 270 men in the 3d Maryland cavalry, 160 men in a battalion of heavy artillery, and 150 in an infantry regiment. To effect these enlistments they circulate all sorts of lies among the prisoners. The chief lies are to the effect that Gen. Lee has resigned — that North Carolina has withdrawn from the Confederacy and sent commissioners from the State on to Washington to make terms for re-entering the Union, and that Virginia is only waiting for Lee’s army to be driven from her borders, to resume her connection with the Yankee nation.

They tell the men if they will enlist they will be sent out West to fight the Indians, and will never be sent South where there would be any danger of their capture. When a prisoner agrees to enlist his name is put down in a book, and he is marched from the main body of the prisoners to another part of the island to join his companions in shame, who live in tents there. He never comes back among his old comrades, for fear, as one of our informants remarked, “we should cut his d — d throat.” They are jeered and hooted by their late companions as they pass out from them. They are termed “galvanized Yankees.”

Our prisoners are dying in Fort Delaware at the rate of twelve a day. Their rations are six crackers a day and spoilt beef.

In a 2010 (I believe) report Kevin Mackie, an undergraduate at the University of Delaware, questioned official reports of the number of escapees from Pea Patch Island during the Civil War and explained conditions there. He estimates between 64 and 103 Confederates escaped. The influx of prisoners from Vicksburg and Gettysburg by August 1863 increased the island’s population to over 12,000 and made conditions worse. By the end of the war over 2400 Prisoners and guards died and were buried “at Finn’s Point cemetery in New Jersey”. The poor living conditions and rampant disease motivated many prisoners to try to escape by crossing the swift current of the Delaware River. And there were other escape methods. For example, one man swapped places with a corpse in his casket. A Floridian is said to have successfully ice skated down the river to freedom.

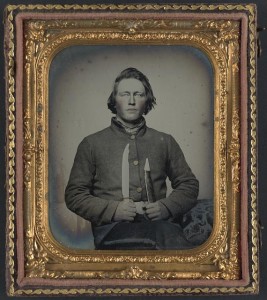

According to the Library of Congress the above photo is of Private Samuel H. Wilhelm of I Company, 4th Virginia Infantry Regiment “who died as POW of acute diarrhea at Fort Delaware, Del., on September 22, 1863.

The image of the prisoners entering Fort Delaware was published in the June 27, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly at Son of the South.