From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in 1863:

The Battle of Gettysburg.

(Correspondence of the Philadelphia Age.)

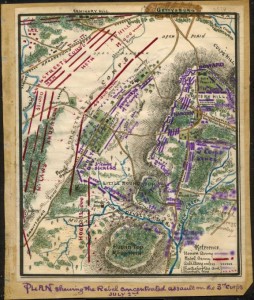

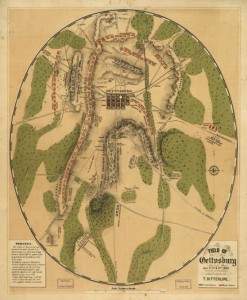

GETTYSBURG, July 7, 1863. – The battle of Gettysburg will be one of the longest remembered of all the battles of this war.It is the only contest fought upon Northern soil. It repelled an invasion. It was sanguinary and desperate. Each armies [sic] had good positions, and what is most anomalous in war, both occupied such advantageous ground that neither could drive the other away. … [Here follows a gap in the copied clipping and then a large section recounting the battle over the three days. We’re picking this up after the rebel charge on July 3rd was repulsed]

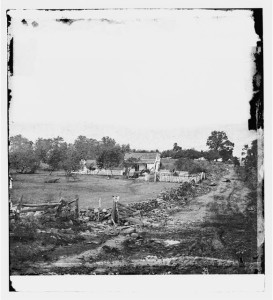

The Federal troops did not chase them. The land back of the seminary was rather flat, and cut up into grain fields, with here and there a patch of woods. The rifle pits on the brow of the hill proved an effectual aid to the Federal soldiers in maintaining their ground; and as they lay behind the bank, with the ditch in front they could pick off the stragglers from the retreating enemy. There was but little serious fighting after that, and night put an end to Friday’s struggle, the Confederates having retired about a mile on the north, near the seminary, and a half a mile on the south, at a little stream.

During the night the dead in the streets of Gettysburg were buried, and the wounded on all parts of the field were collected and and carried to the rear. On the next morning General Meade expected another attack; but instead of making it the enemy retreated further, abandoning their entire line of battle, and the pickets reported that they were entrenching at the foot of South Mountain. The Federal army was terribly crippled and sadly in want of rest, and no advance was made, although pickets were thrown out across the enemy’s old line of battle, and towards the place where they were building entrenchments. All the day was spent in resting and feeding the men. Gettysburg was turned into a vast hospital, and impromptu ones were made at a dozen places in the field. The rain came, too, and with it cool air and refreshment both from wind and rain. No one could tell what the enemy were doing; every picket reported that they were entrenching, and the night of the 4th of July closed upon the field with it in the Federal possession.

THE LOSSES.

It is very difficult to make an estimate of the losses in any contest, but from all that can be learned the number of killed, wounded and captured of the Federal army will scarcely exceed 15,000. The enemy’s loss was about the same. There is no reason why it should exceed that of Gen. Meade, and none which should lead us to place a lower estimate upon it. As to prisoners it is more difficult to judge, but as there were no instances of an entire command surrendering, the only men captured being deserters, stragglers and wounded, who either lagged behind or lay upon the field, the two armies have been equally depleted by captures. The Confederates, however, paroled nearly all who they took, and these are still with Gen. Meade. Of captured Confederates, there seem to have been about six thousand.

AFTER THE BATTLE

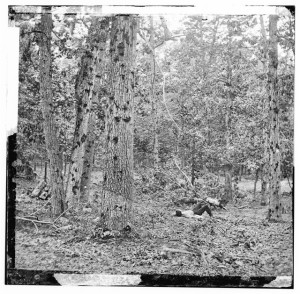

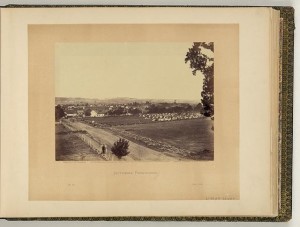

My visit to the field was made this (Tuesday) morning, and it presented a wonderful though sorrowful spectacle for the curious. Most of the dead had been buried but many were still lying about, few, however, being Federal soldiers. Every fence was knocked down, and every house or shed upon the field or around had its roof in tatters. The fences had all been torn down by passing and repassing troops, or else they had been carried off bodily to make barricades or breastworks. The stone previously scattered over the surface of ground had been collected in piles for rifle pits. Nearly every tree had limbs torn from it, and all bore marks of bullets. Some had their bark stripped off in shreds by the wind of passing shells. The ground was tramped into a bog, and was covered with every conceivable thing – old broken muskets, bayonets and ramrods, pieces of wagons, broken wheels cartridge boxes, belts, torn clothing, blankets, fragments of shell, and sometimes unexploded ones, bullets, cartridges, powder – everything used in war or by soldiers was scattered around in plenty. The grain and grass, which once grew there, was almost ground to a jelly. Every where could be seen traces of the carnage. Hundreds of dead horses, still unburied, lay on the field; and in bogg [y?] places and spots distant from the town many of the men were still unburied.

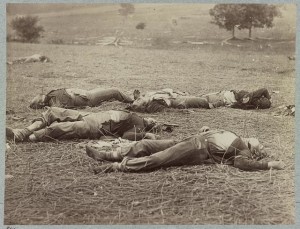

There is something impressive about [a] dead man on a battle-field. To see him lying there with his hands clenched, his teeth set, and his limbs drawn up, with ramrod or musket firmly held – lying just as he was standing when the fatal bullet struck him, teaches a sad lesson. To see scores of them is more impressive; and that with the awful desolation and havoc and ruin on all sides, shows far too plainly for delicate senses the terrible end of battle. To know at this fence where so many lie, a tug of war was had for hours – to feel that the tree whose bark is stripped off showing red stains on the inner wood, has received the gushing blood of some poor soldier, is by far the best teacher of war’s evils. And when after all is over, men still lie on the damp ground, undisturbed as they fell, with hawks, and crows and buzzards sailing lazily over them – their countenances bearing an expression of horror, as the blearing, bloodshot eyes, the blackened face, and the contorted features, turn up towards you – when all this is seen, and the fact that thousands like them have lain there before is impressed upon the mind, a remembrance is left which cannot be effaced. Sermons and precepts may be exhausted in vain; but the lesson taught by a dead man slain in battle, lying in his gore is worth ten thousand holiday exhortations. Yet many look upon it without emotion. Many walked about amid the horrid stench of that field unmoved. They turned over the rubbish, picked up bullets and fragments of shells for mementoes, but that was all. The[y] looked upon the dead, to be sure, but with no expression of pity if he were a Federal soldier, and only a laugh or a curse if he were a Confederate. They forgot that the poor dead man had been led to his death by others more responsible than he.

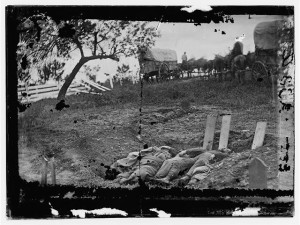

All over the field there are newly made graves. There are long rows of them paralled [sic] to each other, where the Federal soldiers lie. Where the carnage has been great, a trench receives the remains of all; they are thrown in indiscriminately without burial service or coffin. The clothes they wore when killed are their shrouds, and the burial parties, or if not they, the fiends who always prowl about after a battle, rob the dead man’s pockets before they bury him. Nearly every dead soldier’s pockets were turned inside out and rifled of their contents.

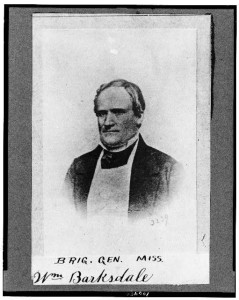

By the side of a hedge on the Emmettsburg road is the grave of the Confederate General Barksdale. It is a plain mound, with rough pine head and foot boards. At his head, written with a lead pencil, is the following inscription.

“BRIG. GEN. BARKSDALE,

“McLaw’s Division, Longsteet’s Corps.

“Died July 3d.

“Wound in left breast – left leg broken,

“Eight years a Representative in Congress.

At the foot, written in the same hand,

“Gen. Barksdale, C.S.A.”

At the Confederate General’s feet, and almost touching him, it lies so close, is the grave of a slain Federal officer. The head board tells us it is captain Foster, of the 148th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. At the captain’s feet is the grave of N.M. Wilson a sergeant of the 11th Massachusetts. There they lie, New England, Pennsylvania and the South, two of them bitter enemies during life, but sleeping their last sleep together on she [sic] soil of their native state.

THE RESULT

So far as the fight was concerned, neither army can be said to have gained any material advantage. To retreat from a field and leave it in the enemy’s possession is technically a defeat and it may be conceded therefore that General Meade gained a victory. Still, Lee’s army was not driven away. It was not routed. It voluntarily fell back at a time when no one was fighting it. Lee began to dig and retreat at the same time; and so well did he hide his manoeuvres, thad [sic] he secured thity-six hours start in his retreat. He retired down both sides of the South Mountain and on Sunday afternoon while pursuit was commenced, there were several skirmishes. Lee got safely away, and unless the high water in the Potomac stops him or he does not wish to cross, he is by this time safely over with the greater part of his army. General Meade is not able to intercept him, and all ideas of his capturing a host of fleeing invaders are foolish.

Still, Gen. Meade has done the best he could. He is a modest, unpretending, brave officer, and has acted wisely, and well. He has done all that lay in his power, and it would be the gravest injustice if fault were to be found with him now because General Lee’s army was not routed or taken.

William Barksdale was mortally wounded on July 2, 1863 as he led his brigade on a “magnificent charge” through the Peach Orchard and on towards Cemetery Ridge. Near Plum Run Barksdale was wounded three times and died the next early morning at a Union hospital.

______________________________________________________

The photograph of the gravestone in Jackson is licensed by Creative Commons

![The battle of Gettysburg--Prisoners belonging to Gen. Longstreet's Corps captured by Union troops, marching to the rear under guard (by Edwin Forbes, [18]63 July 3; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-20557)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/20557r-300x221.jpg)