As the rebel army under General Lee moved north in June 1863, efforts were underway to bolster the defenses of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s state capital. New York sent short-term militia units. Here’s a bit about the experiences of Brooklyn’s 23rd Regiment

New York State Militia (National Guard). The author used self-deprecating humor to point out that the militia men were far from toughened veterans. He found the inhabitants of Harrisburg to be surprisingly complacent. The Brooklynites spent June 20 and 21 digging trenches.

From Our campaign around Gettysburg by John Lockwood:

Thursday, 18th.—The Brooklyn Twenty-Third are ordered to assemble at their armory, corner of Fulton and Orange streets, at 7 o’clock, a.m., fully armed and equipped, and with two days’ cooked rations in their haversacks, to march at 8 o’clock precisely. The gallant fellows are up with the larks: a hundred last things are done with nervous haste; father and brother give and receive the parting brave hand-grip; mother and sister and sweetheart receive and give the last warm kiss; and with wet eyes, but in good heart, we set out for the rendezvous. There is remarkable promptitude in our departure. At the instant of 8 o’clock,—the advertised hour of starting,—the column is moving down Fulton street toward the ferry. The weather is auspicious—the sun kindly veiling his face as if in very sympathy with us as we struggle along under our unaccustomed burden. From the armory all the way down to the river it is a procession of Fairy-Land. The windows flutter with cambric; the streets are thronged with jostling crowds of people, hand-clapping and cheering the departing patriots; while up and down the curving street as far as you can see, the gleaming line of bayonets winds through the crowding masses—the men neatly uniformed and stepping steadily as one. Bosom friends dodge through the crowd to keep along near the dear one, now and then getting to his side to say some last word of counsel, or to receive commission to attend to some forgotten item of business, or say good-bye to some absent friend. As we make our first halt on the ferry-boat the exuberant vitality of the boys breaks out in song—every good fellow swearing tremendously, (but piously) to himself, from time to time, that he is going to give the rebels pandemonium, alternating the resolution with another equally fervid and sincere that he means to “drink” himself “stone-blind” on “hair-oil”. What connection there is in this sandwich of resolutions may be perhaps clear to the old campaigner. To passing vessels and spectators on either shore the scene must be inspiriting—a steamboat glittering with bayonets and packed with a grey-suited crowd plunging out from a hidden slip into the stream, and a mighty voice of song bursting from the mass and flowing far over the water. To us who are magna pars of the event, the moment is grand. Up Fulton street, New York, and down Broadway amid the usual crowds of those great thoroughfares, who waved us and cheered us generously on our patriotic way, and we are soon at the Battery where without halting we proceed on board the steamboat “John Potter” and stack arms. There is running to and fro of friends in pursuit of oranges and lemons—so cool and refreshing on the hot march—and a dozen little trifles with which haversacks are soon stuffed. One public-spirited individual in the crowd seizes the basket of an ancient orange-woman, making good his title in a very satisfactory way, and tosses the glowing fruit indiscriminately among the troops, who give him back their best “Bully Boy!” with a “Tiger!” added. Happy little incidents on every side serve to wile away a half hour, then the “all a-shore!” is sounded, the final good-bye spoken, the plank hauled in, and away we sail. A pleasant journey via Amboy and Camden brings us to Philadelphia at the close of the day. There we find a bountiful repast awaiting us at the Soldiers’ Home Saloon, after partaking of which we make our way by a long and wearisome march to the Harrisburg Depot. At night-fall we are put aboard a train of freight and cattle cars rudely fitted up, a part of them at least, with rough pine boards for seats. The men of the Twenty-Third Regiment having, up to this period of their existence, missed somehow the disciplining advantages of “traveling in the steerage,” or as emigrants or cattle, cannot be expected to appreciate at sight the luxury of the style of conveyance to which they are thus suddenly introduced. But we tumble aboard and dispose ourselves for a miserable night. A few of us are glum, and revolve horrible thoughts; but the majority soon come to regard the matter as such a stupendous swindle as to be positively ridiculous. They accordingly grow merry as the night waxes, and make up in song what they lack of sleep.

Friday, 19th.—The darkest night has its morrow. We reach Harrisburg thankfully a little after daybreak, and bid adieu, with many an ill-suppressed imprecation, to the ugly serpent that has borne us tormentingly from Philadelphia. Just sixty-four hours have elapsed since the orders were promulgated summoning the Brigade to arms. We are marched at once to Camp Curtin, some three miles out of town, and in the afternoon countermarched to town and thence across the Susquehanna to the Heights of Bridgeport—the latter being accomplished through a rain storm. As we enter the fort the Eighth and Seventy-First, N.Y.S.N.G., which had got a few hours’ start of us, move out, taking the cars for Shippensburg on a reconnoissance.

II.

CAMP LIFE ON THE SUSQUEHANNA.

In hastening thus to the rescue of our suddenly imperiled government, we gave ourselves to that government without reserve, except that our term of service should not be extended beyond the period of the present exigency. Ourselves stirred with unbounded enthusiasm as we fell into line with other armed defenders of the Fatherland, we expected to find the inhabitants of the menaced States, and especially the citizens of Harrisburg, all on fire with the zeal of patriotism. We expected to see the people everywhere mustering, organizing, arming; and the clans pouring down from every quarter to the Border. At Harrisburg a camp had indeed been established as a rendezvous, but no organized Pennsylvania regiments had reported there for duty. The residents of the capital itself appeared listless. Hundreds of strong men in the prime of life loitered in the public thoroughfares, and gaped at our passing columns as indifferently as if we had come as conquerors, to take possession of the city, they cravenly submitting to the yoke. Fort Washington, which we were sent to garrison, situated on what is known as Bridgeport Heights, we found in an unfinished state. In the half-dug trenches were—whom, think’st, reader? Thousands of the adult men of Harrisburg, with the rough implements of work in their hands, patriotically toiling to put into a condition of defence this the citadel of their capital? Nothing of the sort. Panic-stricken by the reported approach of the enemy, the poltroons of the city had closed their houses and stores, offered their stocks of merchandize for sale at ruinous prices, and were thinking of nothing in their abject fear except how to escape with their worthless lives and their property. In vain their patriotic Governor, and the Commander of the Department of the Susquehanna—his military head-quarters established there—sought to rally them to the defence of their capital. Hired laboring men were all we saw in the trenches! What a contrast to this the conduct of the Pittsburghers presents! They too had a city to defend—the city of their homes. The enemy threatened it, and they meant to defend it. Their shops were closed; their furnace and foundry fires, which like those watched by the Vestals had been burning from time immemorial, were put out; and the people poured from the city and covered the neighboring hills, armed with pick and shovel. “Fourteen thousand at work to-day on the defences,” says the Pittsburg Gazette of the 18th June. Such a people stood in no need of bayonets from a neighboring State to protect them; while the apathy of the Harrisburghers only invited the inroads of an enterprising enemy.

And so the Twenty-Third was ordered into the trenches! This was so novel an experience to the men that they took to it pleasantly, and for two days did their work with a will. It must have been amusing, however, to an on-looker of muscle, in whose hands the pick or spade is a toy, to watch with what a brave vigor hands unused to toil seized and wielded the implements of the earth-heaver; and how after a dozen or two of strokes and the sweat began to drop, the blows of the pick grew daintier, and the spadefuls tossed aloft gradually and not slowly became spoonfuls rather. But we rallied one another and dashed the sweat away; and again the picks clove the stony masses damagingly, and the shovels rang, and the parapets grew with visible growth. Gangs of men relieved each other at short intervals; and in this way we digged through Saturday and Sunday.

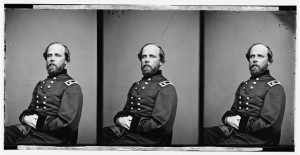

After Chancellorsville Darius Nash Couch “requested reassignment after quarreling with Hooker. He commanded the newly created Department of the Susquehanna during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863. Fort Couch in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania, was constructed under his direction and was named in his honor.”