Not exactly the Union objective

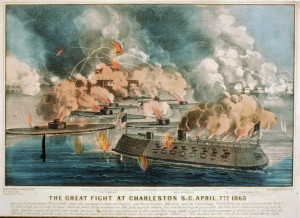

150 years ago yesterday a federal fleet commanded by Samuel F. Du Pont tried to take a first step toward capturing Charleston, South Carolina by attacking Fort Sumter. The attack was unsuccessful.

From The New-York Times April 13, 1863:

CHARLESTON.; Our Own Accounts of the Attack On Fort Sumter. The Iron-Clads Under Fire Two Hours. They Endure a Concentric Fire from Five Different Points for Thirty Minutes. Thirty-five Hundred Shots Fired by the Rebels. ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY IN A MINUTE. The Passage of Fort Sumter Prevented by Obstructions. Five of the Monitors Only Slightly Damaged. THE KEOKUK RIDDLED AND SUNK. THE CASUALTIES VERY LIGHT. CASUALTIES ON THE NAHANT. CASUALTIES ON KEOKUK.

BALTIMORE, Sunday, April 12, 1863.

I have just reached this point from Charleston Harbor via Fortress Monroe, by the gunboat Flambeau, bringing official dispatches from Admiral DUPONT.

The iron-clad fleet, in its attack on Fort Sumter, has met with a repulse, but not a disaster. The attack was made on the afternoon of Tuesday, the 7th inst., and continued for two hours and a half. The fleet had all been got over the bar the day previous, and lay at anchor in the main ship channel along the shore of Morris Island, at a distance of about a mile.

The line of battle was formed in the following order:

1. The Weehawken, Capt. J. RODGERS.

2. The Passaic, Capt. PERCIVAL DRAYTON.

3. The Montauk, Commander J.L. WORDEN.

4. The Patapsco, Commander D. AMMON.

5. The Ironsides, Commander T. TURNER.

6. The Katskill, Commander G.W. RODGERS.

7. The Nantucket, Commander D. MCN. FAIRFAX.

9. The Nahant, Commander J. DOWNS.

9. The Keokuk, Commander A.C. RHIND.

The Ironsides was Admiral DUPONT’s flag-ship.

The official order was to pass the batteries on Morris Island without returning their fire, and pass inside of Fort Sumter, and devote themselves to bombarding Fort Sumter at a distance of from six to eight hundred yards.

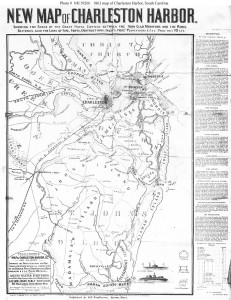

At 2 o’clock the head of the line was in motion, the rest following. The batteries on Morris Island did not open on the fleet at all, and the enemy made no fire until the fleet had reached a position between Forts Sumter and Moultrie, when a terrific broadside came from the barbette guns of Sumter. At the same time the batteries on Cnmmings Point and Sullivan’s Island opened, and the iron ships were exposed to a concentric fire from five different points, unparalleled in the history of warfare.

The fleet found it impossible to pass up beyond Fort Sumter and assume to appointed place, owing to obstructions, which extended across the entire channel from Sumter and Moultrie, while above these, near the middle ground, were three other rows of piles, and above these three rebel iron-clads. The fleet was thus compelled to sustain this terrific fire, and nobly it did so, for thirty minutes. During that time not less than thirty-five hundred shots were fired by the enemy, one hundred and sixty being counted in a single minute.

At the end of this time five of the nine iron-clads were found to be more or less disabled, and at 4 o’clock the flagship signaled to retire.

The Keokuk, with splendid audacity, had run up to within five hundred yards of the fort, and near her was the Katskill. The whole fleet devoted themselves to Fort Sumter; but, owing to the limited time the ships were enabled to remain, comparatively few shots were fired.

The Ironsides, caught in the tide, was in great part unmanageable. In consequence, Admiral DUPONT had to signal to the fleet to disregard the movements of the flag-ship.

The iron-clads received each from twenty to ninety shots. The Keokuk was the worst used up, receiving several shots below and above the water line. The other four, though in reality but slightly injured, were yet rendered temporarily unfit for use. They will speedily be repaired. The Keokuk was, however, so badly damaged that she sunk this morning in the position near her original anchorage. She will be blown up, to prevent her falling into the hands of the rebels.

Fort Sumpter shows some ugly pock marks on her eastern face.

The land force had been landed on Folly Island, near Stono, but did not co-operate in the attack.

The attack should really be regarded in the light of a reconnoissance, and though it was not successful, yet it was not as disastrous as it might have been. When you learn the full details you will see that the result is, on the whole, far from discouraging.

Commander J. Downs, Massachusetts, slight contusion of foot, from piece of iron, loosened in pilot-house.

Pilot Isaac Scofield, New-York, severe contusion neck and shoulders, from flying bolt in pilot-house. Is doing well.

Quartermaster Edward Cobb, Massachusetts — compound fracture of skull from flying bolt in pilot-house. He has since died.

John McAllister, seaman, Canada — concussion of brain from flying bolt in turret. Doing well. …

… The advantage of our fleet being in possession of the main ship channel, narrows the circuit of the blockade two-thirds of the former distance. None of the batteries fired upon our vessels until the latter reached the vicinity of the main forts.

In reviewing this battle the Harper’s Weekly of April 25, 1863 (provided by Son of the South) admitted a Union failure that “insures an indefinite prolongation of the war”. But the blessing in disguise was that the people of the North were becoming a tougher, more persevering people in their effort to keep the Union together:

No one who watches the public mind can have helped observing the improvement which we are making in stoutheartedness. A few months ago a little defeat depressed us woefully, and depreciated the currency six to eight per cent. Now, the public accept defeats as well as victories as the natural incidents of war, and are neither excessively depressed by the one nor unduly elated by the other. Du Pont’s repulse at Charleston, which was certainly not palliated or glossed over in the accounts in the papers, gave rise to no despair, to no abuse of Du Pont or the Government, and barely caused a flutter in the gold market.

This nation is being educated to its work. The race of ninety-day prophets—who did us so much harm at the beginning, and made us so ridiculous abroad—is about extinct. No one now undertakes to say how soon we shall crush the rebellion. But no one doubts that we sh[a]ll do so sooner or later. We may meet with more repulses …

The USS Keokuk had a very short career. It sailed out of New York harbor on March 11, 1863 and sunk in Charleston Harbor on April 8, 1863 as a result of the shelling it took during the April 7th battle.

Having joined the U.S. Navy in 1815, Samuel Francis Du Pont had a very long career, but Charleston took a toll on him, too:

The Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, blamed Du Pont for the highly publicized failure at Charleston. Du Pont himself anguished over it and, despite an engagement in which vessels under his command defeated and captured a Confederate ironclad, was relieved of command on July 5, 1863, at his own request. Though he enlisted the help of Maryland U.S. Representative Henry Winter Davis to get his official report of the incident published by the Navy, an ultimately inconclusive congressional investigation into the failure essentially turned into a trial of whether Du Pont had misused his ships and misled his superiors. Du Pont’s attempt to garner the support of President Abraham Lincoln was ignored, and he returned home to Delaware. He returned to Washington to serve briefly on a board reviewing naval promotions.