Actions speak louder than “animus”

One of the weaknesses of the Confederate conscription acts is said to have been widely abused exemptions. Here a Confederate judge decided against two native Virginians who claimed exemption on the ground that they were domiciled in Washington, D.C. when the war began. It seems their case was greatly weakened by the fact that they volunteered for Confederate service just after Fort Sumter and served for over a year.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch February 25, 1863:

A Legal opinion of the Conscript act — highly important decision.

A habeas corpus case, involving more questions of general interest than any which has yet been brought before the country, was decided by Judge Meredith yesterday, after elaborate and protracted argument. It involves the right of the Government to the military services of a large number of able-bodied residents of the Confederacy, between the ages of eighteen and forty, who have heretofore been considered as exempt from military duty. The facts are briefly as follows:

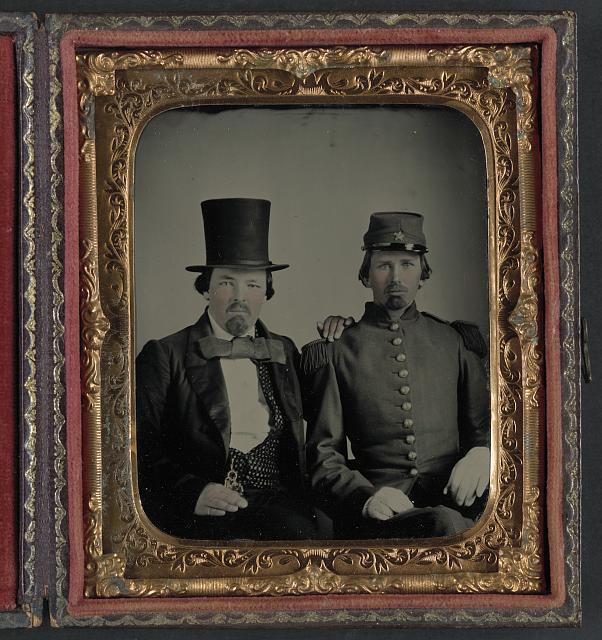

William and Charles P. Harman at the commencement of the existing war were living in the District of Columbia with their father, who had in the year 1855 removed from Alexandria to Washington, in consequence of having received an appointment of clerk in one of the departments of Government. His sons were born in Virginia, and at the commencement of the war one was of age and the other a minor. In April or May, 1861, both of them enlisted in a volunteer company, and entered the military service of the Confederate States. They served for twelve months and ninety days, and then claimed their discharge upon the ground of [not?] being of the Confederate States. The validity of their claim was conceded by Col. Taliaferro, the enrolling officer for the Ch[a]rlottesville district, and they were furnished with exemption papers. They were, however, subsequently arrested by order of the Colonel of the regiment in which they had served, and held to military service under the conscript act of April 16, 1862.

The petitioners appealed for and obtained writs of habeas corpus for the purpose of ascertaining whether they were liable to military duty as “residents” of the Confederacy. In the hearing of the case, before Judge Meredith, Hon. Shelton F. Leake appeared for the petitioners, and made use of the various points bearing upon the case, to procure their discharge. P. H. Aylett, E[s]q., Confederate States District Attorney, appeared for the War Department, and resisted the application for the discharge of the petitioners. The argument on both sides was able and elaborate.

Judge M[e]redith delivered a long and able opinion, in which he sustained with much force and learning the points made by the counsel for the Government. He decided that the removal of the petitioners’ father to Washington to accept a clerkship in the Post-Office Department had not changed the domicil either of the father or of his family, as the office was one revocable at the will of the appointing power, and that the residence of the petitioners there was from “necessity,” arising from the authority of the father. He also decided that, admitting the father of the petitioners to have acquired a domicil in Washington, the petitioners, as native-born Virginians, had, at the commencement of the war, an undoubted right to resume their native citizenship, and that by returning to the domicil of their origin, and by taking up arms to fight our battles, they had furnished the highest and most conclusive evidence of their voluntary resumption of their rights as citizens of Virginia — Against such acts as these the Judge said that more declarations of the animus of the petitioners should not be permitted to weigh.

Judge Mer[e]dith commented on and sustained the point (made by Mr. Aylett) that the domicil of the soldier was that of the country in whose service he was enlisted. Nothing, he said, could be clearer than that by entering the military service you acquire a domicil. He cited and commented upon a large number of interesting decisions in England, France, Germany, and America, to show that no principle of law was more clearly established than the one contended for by the counsel for the Government, and expressed the opinion that every citizen of Maryland and every foreigner who had once enlisted in our armies, it mattered not for how brief a period, was a fit subject for conscription, if between the ages of eighteen and forty, and he expressed the hope that the War Department would at once all persons thus liable.

The language of this Conscript act, the learned Judge said, was exceedingly broad. It evidently contemplated the conscription of all “residents” in the Confederate States between the specified years. Whether they were residents in pursuit of pleasure, money, or what not, they were clearly liable, under the broad language of the act, and should be conscribed. The Judge also decided that the War Department could disregard all exemptions which had been given by enrolling officers where they had been improperly given. The petitioners, he decided, were not held at this time in custody of the proper official, and were therefore entitled to their discharge; but it was strictly legitimate and proper for the proper enrolling officer for the Albmarie district to enroll them as conscripts, and make the proper disposal of them under the provisions of the Conscript act of 16th April, 1862.

It is understood that no appeal will be taken from this important decision, and the action of the War Department and of the numerous enrolling officers will doubtless conform to it.

And appeal options were limited. Although the Confederate constitution allowed for a Supreme Court, it was never set up because of the “ongoing war and resistance from states-rights advocates, particularly on the question of whether it would have appellate jurisdiction over the state courts”.