A pro-Union editorial saying that Northerners who propose compromise and peace are really supporting Disunion because the South is never going to willingly rejoin the Union, with or without guarantees for slavery. Because the Administration has settled on its anti-slavery policy as part of its war strategy, those who publicly oppose Emancipation are actually opposing the war effort itself.

From The New-York Times February 2, 1863:

The Political Future Bolder Positions and Clearer Issues.

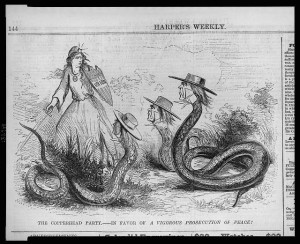

The Northern auxiliaries of JEFF. DAVIS must soon give up their bush-fighting. It has served them a good turn. They owe to it all their success hitherto. But it could not last. No sort of bushwhacking ever does. People come to understand it, and when it is understood there is an end of it. Counterfeited flags, stolen uniforms, false alarms, decoys, traps, ambuscades, doublings on the track, and all the other means of deception, known to the political guerrilla quite as well as to any other, after a while — especially in earnest times like these — lose their effect. There is no alternative, then, but to take a little more courage, and change to regular warfare. This transition is now going on. These rebel allies are gathering fresh boldness every day, and are fast ranging themselves under their true colors in the open field. We may expect straightforward battle from them soon. It will be this political battle, quite as much as any other, that will decide the fate of the Union.

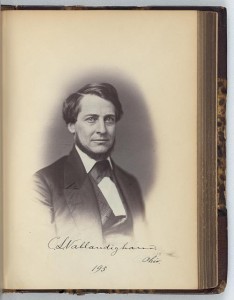

The political controversy has at last come to this supreme and plain issue: War and Union, or Peace and Separation. All other issues have dwindled, and are fast disappearing. People have differed about the Emancipation Proclamation, about arbitrary arrests, about the financial policy of the Administration, about the comparative merits of different Generals, and about many other matters, and the rebel sympathizers of the North have done their best to magnify these differences and turn them against the Government. It was the consummate art with which this variance was stimulated, under false professions of devotion to the war and the Union, that was the chief agency in giving the Fall elections their strange results. But their management no longer answers its purpose. Its impelling motive is at last understood; and so, too, is its fatal tendency. All true National men are agreeing to bury these differences, and bend their energies to the one great end of crushing the rebellion. All others are going over outright to an Anti-War position, and acknowledging the leadership of VALLANDIGHAM, COX, and their compeers, who have opposed the war from the outset — who opposed it while MCCLELLAN was still Commanding-General, while the Administration was doing its utmost to prevent interference with the slaves, and long before such a thing as arbitrary arrest, in a loyal State, was heard of or thought of. Thus the parties are consolidating. Every man will speedily have to find his place on the one side or the other.

The day of the supreme test of devotion to the country has come. An absolute sacrifice of every extraneous consideration is required. The time has passed for conditional loyalty. The man who subordinates his present patriotic duty to this or that favorite object or favorite policy of his own, thereby proves himself a false man, and, at heart, no better than a traitor. The Government, after long deliberation, has fixed its war policy in reference to Slavery. While that policy was under consideration it was a fair subject for public discussion. It was discussed everywhere and thoroughly. In the light of that discussion, as well as of the new developments of the war, the Government settled upon its action. There is not the slightest ground for believing that this action will be reversed, or materially modified. It is no longer an open question. The policy, wise or unwise, is henceforth an inseparable part of the war itself. If there [b]e those who don’t like it, it is their duty to acquiesce in it. To stand out against it, in this stage of the matter, is practically equivalent to opposing the war itself. This, in effect, is nothing more or less than making the preservation of the nation subordinate to the preservation of Slavery; for it is certain that without further war the rebellion must prevail, and the nation go down.

Of course, acquiescence in the general war policy of the Administration need not impose silence as to the practical conduct of the war. Whatever use the Government may choose to make of its war power in relation to Slavery, it is bound, none the less, to take care that the war itself is prosecuted with all possible skill and vigor. If it fails in this, its best friends may consistently rebuke it; nay, their duty is so to do. The more devoted one is to the war, the more faithful ought he to be in protesting against its delays and its blunders. There is all the difference in the world between such anxiety to have the war prosper, and the desire that it should be abandoned; though similar criticisms may often be prompted by both feelings. The rebel sympathizer does all that he can to render the war unpopular, and this makes it all the more the duty of every loyal man to do all that he can, both by word and act, to render it successful.

The idea of compromise has been a mockery and a snare from the beginning; but we owe it to the candor of the rebels that it is now better understood. They have always declared that they will never consent to reunion; but at no time with greater emphasis than since the election successes of the opponents of the Administration. They hailed those successes simply as the harbingers of the acknowledgment of their independence. Not a public journal, nor a public man in the Confederacy gave them any other construction. Not one of them, so far as is known here, with whatever antecedents, has ventured to admit either the desirableness or the possibility of taking new guaranties for Slavery, and coming back into the Union. They have all unanimously scouted it — and not only in the most positive, but in the most contemptuous manner. They no longer know the word compromise, and it is high time it should be dropped out of our own political vocabulary. Even if we were abject enough to entertain the question, War or Compromise? the chance is denied us. Our only choice is between War and Disruption. Our political contests from this time on to the end must be fought on that ground only. The South, precisely because it made Slavery its supreme consideration, sacrificed the Union. Those in the North, who also make Slavery the first consideration, consistently join in the same parricidal work. It has had to come to that. There is no middle ground.

Here, then, is the real issue. All true public men should mark it, and stand unflinchingly up to it. There should be no dissensions among them, no invidious references to the past. Agreeing upon the vital matter of sustaining the war, and with it the present Anti-Slavery war policy, as now the sole means of saving the unity of the nation, they should be united as one man, and hold firm to the end against traitors and the abettors of traitors. They will triumph in the end, as surely as there is a faithful people around them, and a just Heaven above them.