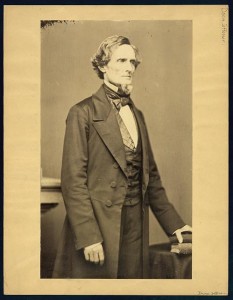

On December 10, 1862 Confederate President Jefferson Davis left Richmond for a tour of the western states, the western seats of war. He returned to Richmond on January 5, 1863:

He was weary and he looked it, and with cause, for in twenty-five days he had traveled better than twenty-five hundred miles and had made no less than twenty-five public addresses, including some that lasted more than an hour. However, his elation overmatched his weariness, and this too was with cause. He knew that he had done much to restore civilian morale by appearing before the disaffected people, and militarily the gains had been even greater. …

Davis himself had done as much as any man, and a good deal more than most, to bring about the result that not a single armed enemy soldier now stood within fifty air-line miles of any one of these three [Richmond, Vicksburg, Chattanooga] vital cities. [1] …

President Davis gave an impromptu State of the Confederacy speech when he was serenaded by some Richmond citizens. He paralleled Virginia in the Civil War with Virginia in the Revolution and could point out that the heroic general Robert Lee was the son of “Light Horse Harry”.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch January 7, 1862:

The President Welcomed Keme [Home] — Serenade and speech.

–On Monday night, about 11 o’clock, some two or three hundred persons assembled at the President’s mansion, with Smith’s Band, for the purpose of paying their respects to the executive head of the Confederacy on his return from an extended tour. After the band had played two popular airs the President appeared at the door, and the crowd gave a cheer, when the gentleman who accompanied him said: “Fellow-citizens, allow me to introduce to you the President of the United States.” There was a momentary silence, when the presenter corrected himself by saying “the President of the Confederate States” This was more satisfactory, and Mr. Davis remarked that he was proud to acknowledge that title, but the other be would spurn. He then gracefully thanked his friends for this manifestation of their regard, and expressed his pleasure at meeting them again on his return to the capital of the Confederate States, in a Commonwealth which has been the size [scene] of the bloodiest battles of two revolutions in defence of the principles of liberty. Now, he believed, the incentive to fight was even stronger than when our forefathers threw off the yoke of tyranny; for they had an open and manly foe, while our enemies come as savages and murderers, despoiling the homes of the living and the graves of the dead. Any further association with Yankees was looked upon with loathing and horror, and even the companionship if hyenas could be more readily tolerated by the people of the South. He spoke of the recent victories of our armies, as having caused the brightest sunshine to fail upon our cause. One year ago many of us were despondent; but now mark the difference — The gallant Lee, who partakes largely of the noble characteristics of his father, “Light Horse Harry,” of the Revolution, has repeatedly driven back the invaders of your soil, and recently, when they gathered for their mightiest effort, at Fredericksburg, they were again hurled back, and suddenly stopped in their movement “on to Richmond”–Some of them did come to Richmond, and he hoped every battle would bring a few of those disarmed and discomfited heroes, prisoners, not conquerors, So, too, in the West; at Murfreesboro’ another brilliant achievement has just been performed, and at Vicksburg the enemy is thwarted in his gigantic project for opening the navigation of the Mississippi. This, he believed, would dampen the order [ardor] of the people of the Northwest, to whom the Mississippi was indispensable as an outlet of trade, and he predicted the most beneficial effects from it. The present, however, was no time to relax our efforts. The enemy must be everywhere met with unflinching courage and resolution and our victorious armies would in time conquer a peace. The resources of the South, developed during the war, had astonished the world, and he believed they would continue to increase, as long as we were engaged in hostilities. The President paid a high compliment to the women of Virginia, which was appreciated by the few who were in attendance. He spoke of their devotion to the sick and wounded soldiers, representing every State in the Confederacy, and from thousands of brave hearts the prayer now ascends. “God bless the women of Virginia” With such women at home, and such soldiers in the field, the eventual success of our cause is inevitable. He spoke of the pleasure it would give to mingle socially with the people of Richmond, but the dares [duties?] and anxieties of his position left little leisure for the indulgence of the finer feelings of nature. In days to come, however, when our independence shall have been achieved and the angel of peace spreads her bright wings over the land, it would be his delight to know more of a people to whom he was indebted for so many acts of kindness. At the close of his remarks, the President invoked the blessing of God upon our cause and people, and bade his audience “good night”

This is but a more sketch of the eloquent address, which was delivered with deep feeling and elicited present cheers. After the President retired the band performed a few more places [pieces] , and the through [throng?] separated, well pleased with the incidents of the occasion.

- [1]Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Volume II Fredericksburg to Meridian (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), 19-20.↩