As a new year began journalists North and South discredited each other and saw good things for 1863 if their respective peoples persevered in the war efforts. Here’s a couple excerpts.

From The New-York Times January 1, 1863:

The New Year and the War.

In our review, yesterday, of our military successes during the year that has closed, it was made very apparent that the rebellion could not survive another twelvemonth of similar experience. It was shown that the reduction of a like amount of territory to the old flag in 1863, as in 1862, would literally wipe the Confederacy from the face of the earth. Considering the present magnitude and splendid condition of our army, and the superb fleet of gunboats just completed — which will not only be able to gain possession of the three remaining Southern ports, but to ascend the Southern rivers far into the interior — it is certainly not unreasonable to believe that the restoration of the National authority can proceed, to say the least, as rapidly hereafter as it has heretofore.

We are too apt to estimate the prospects of the rebellion, not by its actual fortunes, but by the loud tone of its leaders and organs. The rebel Government, and all the newspapers, are protesting with greater vehemence than ever, that submission to “the old concern” is a thing utterly impossible; that the last dollar of property and the last drop of blood shall first be spent. This kind of talk is rather imposing, but, allowing it to be ever so earnest, it really deserves no more heed than the wind. Nothing is more common than for men to protest, even when nearly exhausted, more loudly than ever that they will die sooner than give in. …

We may allow the spirit of the South to be ever so resolute, yet it is no index whatever of what is to be the length of the war. This is not a question of disposition or of purpose, but a question of resource and of ability. We may rely upon it that the rebel leaders will maintain the conflict just as long as they have it in their power to deal a blow. When the people behind them are once thoroughly penetrated with the conviction that further resistance is absolutely ruining them, and not until then, shall we hear them solicit peace. It takes time to produce the results which are to work this conviction; but the conviction itself, when it once fairly comes home, will be sudden in its manifestation and speedy in its effects. We shall probably see the rebellion one month all defiance, the next all submission. We are to judge of its duration by the effective causes at work against it, not by its present temper; by the superiority of our armies in numbers and equipment — by the impossibility, that the rebels can raise another army, when their present one is destroyed — by the power of injury possessed by the naval expeditions — by the hardships inflicted by the blockade — by the constantly increasing financial straits — and not by any tone however lofty, or any spirit however obstinate.

We may take it for granted that this war, like others, will run to its legitimate termination — the disablement of the weaker party — and will then stop. When that point is once reached, the Southern people, as every other people under like circumstances have done, will acknowledge and act upon the necessities of the case. The final pacification will be the less difficult, because it will involve no humiliating terms, such as the worsted belligerent usually has to accept. Nothing more can be required than a renewed acceptance of the Constitution of our fathers — devotion to which is a glory, not a shame. Yet we don’t pretend this resumption of allegiance will be altogether easy. A certain sullenness must continue for months, perhaps for years. We shall never look for such a display of jubilation at the South over the restored Union as that which signalized the return of the Stuarts to the English throne …

But it is useless to speculate about these sequels. It is enough to know that the business of the present year is strenuous, unremitting war. There are the strongest reasons for believing that if the Government, the army and the now loyal people are faithful in this, the old flag will wave triumphantly in every State and County in the land before the year closes. But if instead of faith and harmony and tireless energy, we are to have despondency, distraction and delay, there is no depth of discomfiture and shame to which the year may not reduce us.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch January 1, 1863:

Beware of false confidence.

The people of the Confederate States are buoyant with the hopes excited by the late great victory at Fredericksburg, and the stunning effect which it evidently produced upon the entire Yankee nation. Already we see signs of returning to that condition of false security which proved so nearly fatal after Manassas, and which has on other occasions so materially injured the cause. If we could hope to be heard in quarters where our counsel would be of avail, we would protest against in such feelings agreeable as they doubtless are and tempting as they must be, to men whose have been so long wound up to the utmost degree of ten[s]ion. It is persisely [precisely] from this disposition to relax that the greatest danger is to be apprehended. It is exactly in the very moment of victory that the danger in question is most apt to us. Let us, then, still keep on the alert. Let us exert our energies to their utmost, precisely as though we had been defeated in every engagement, and had the foe thundering at the very doors of our Capital as we had him last summer. The Yankees were stunned, dispirited, overwhelmed for the moment by the [?] at Fredericksburg, but already they begin to recover, and cry for another “On to Richmond” We published an article yesterday from the Philadelphia Press.– paper — in which a new route is mapped off for the advance in which the possiblity of defeat forms not the smallest item of the calculation. In which the capture of Richmond and the “suppression of the reb[e]llion” are spoken of as future events with as much confidence as though the Yankee forces had never met with a check in attempting it. Burnside has already made half a dozen reports, in the last of which he cuts down the number of his killed to 1,152, and his wounded to about 9,000. He is endeavoring, at the instance no doubt of his employers, to raise the Yankee mind from the aby[s]s of despair into which it seems to have fallen, and to prepare it for new enterprises.

We may be assured that the whole Yankee press will join in this endeavor, and that it will be successful. In a fortnight universal Yankeedom will believe that the defeat at Fredericksburg, like the defeat at Sharpsburg, was a great triumph …

We are, at present, pressed nowhere but in the Southwest. The enemy evidently will not make another attempt to take Richmond winter. We have three whole months at least ress the conscription. If fully carried out it will give us — with the army now in the field–700,000 men for our operations in the spring, all of them between the ages of 18 and 40. … Let our authorities do their utmost to bring it all out and, depend upon it they will bring out enough to insure peace, and a glorious peace, before the end of the summer. They will bring out enough to render all the Yankee expenditure abortive; and when this levy shall have been battled they will never be able to raise another. We have a Secretary of War who brings with him a high reputation — no doubt well deserved — for talents, and business qualifications. His advent to office has been most suspicious. It has already been marked by the greatest battle and the most signal triumph of the whole war. Let us hope that his administration will be as fortunate to the end as it has been in the commencement, and — that it may be so — that he will devote all the energies of his mind to the organization of the conscription, and the rendering it efficient. But to this end something more is requisite than even the acknowledged abilities of the Secretary. A should be established in connection with and under the control of his office, to be devoted especially to this one object and it should be filled by the ablest man it is possible to find. He should have no other business but that connected with the conscription. The Governors of the States, and all magistrates and civil officers of every description, should be appealed to in the most earnest terms to lend all the assistance which their offices enable them to lend. Thus only can we raise a force to encounter the million of men about to be hurled against us. Thus only can we render this last gigantic effort abortive. Thus only can we an honorable, a beneficial and a lasting peace. That peace, if these conditions be observed, is right at hand; if they be not observed, it is infinitely distant.

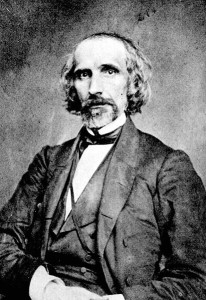

The photo of James Alexander Seddon is licensed by Creative Commons.

As you can tell by the description at the Library of Congress the sheet music was probably published sometime in 1863 after Joseph Hooker was promoted to lead the Army of the Potomac.