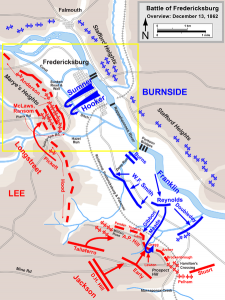

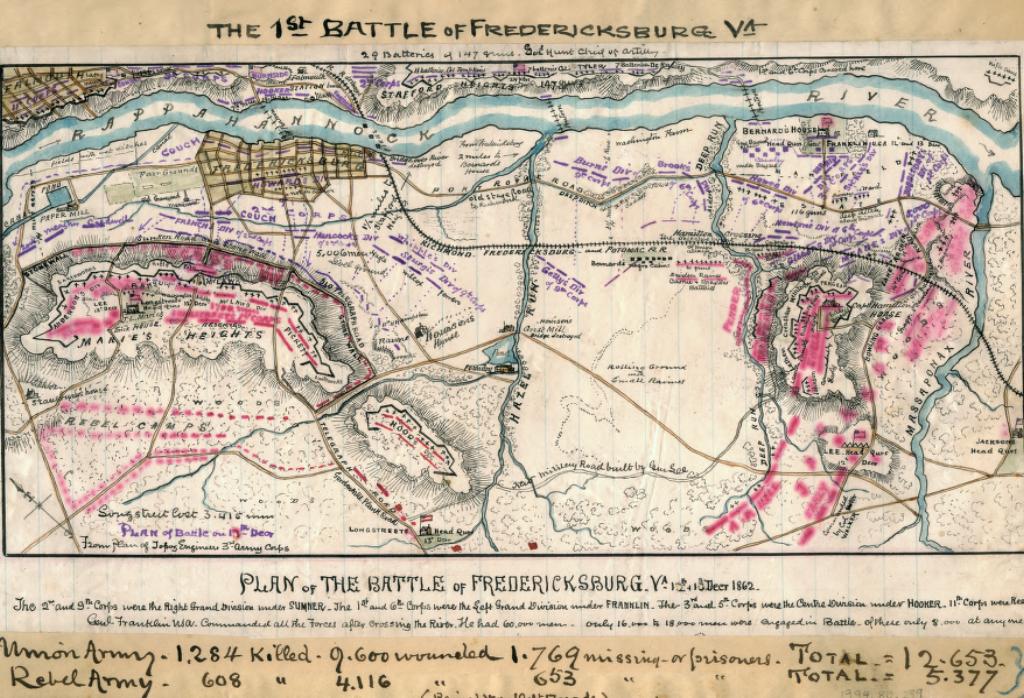

150 years ago today a great Union blood bath occurred at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Belonging to W.F. Smith’s XI Corps, the 33rd New York Infantry Regiment supported artillery in William Franklin’s Left Grand Division. A quick recap of the battle: Franklin’s grand division failed to exploit a temporary breakthrough by troops under Gordon Meade. The Union right futilely tried many times throughout the day to dislodge Confederates concentrated behind a stone wall on Marye’s Heights.

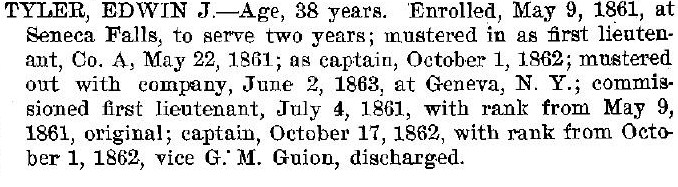

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in 1862:

Letter from Capt. Tyler.

The following letter was written by Capt. E.J. Tyler, the second day after the battle of Fredericksburg. It is dated Dec. 15th, and addressed to his father:

We have been to the front for two days, most of the time supporting the batteries, and under a fierce fire of artillery. Our Brigadier-General (Vinton) is severely if not fatally wounded, and the Brigade is now under Gen. Neil. The 33d is fortunate, as usual, in slight loss. The Brigade I think will lose lightly; but as a whole, there has been some beautiful and sharp fighting as I ever saw. We have driven them back from the river about two miles, into their fortified position, and they are yet fighting like the very devil. We tried them with our best troops for two days, and our men fought desperately and none ever fought better, but still they hold most of their line of defences. Our loss much be much greater than theirs for they fought most of the time under some sort of cover.

Our division was relieved this morning before daylight, and are now in the rear to get a little rest, which gives me his opportunity to say all right with me, and none seriously hurt in the company thus far.

The weather has moderated and is much warmer, and snow has disappeared.

Hastily, E.J. TYLER.

At Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862 Francis Laurens Vinton “…was severely wounded while leading his regiment in a gallant charge. Disabled by his wound for many months, and incapacitated for further service, he resigned from the Army in May, 1863.”

Here’s an excerpt from The story of the Thirty-third N.Y.S. vols.; or, two years campaigning in Virginia and Maryland (by David W. Judd (page 248)) that describes the 33rd’s experience during the battle:

Instead of being posted some distance to the rear Colonel Taylor was ordered close up to the guns and the men lay almost beneath the caissons. Shot and shell were whizzing, screaming, crashing, and moaning all around them, but they manfully maintained their position, receiving the fire directed upon the artillerists. Towards noon a 64-pounder opened from the hill directly back of Fredericksburg. The first shell struck a few feet in front of the Regiment, the second fell directly in their midst, plunging into the ground to the depth of three feet or more. The enemy had obtained most perfect range, and would have inflicted a great loss of life, had not the monster gun very fortunately for us exploded on the third discharge. The guns which the Thirty third supported were repeatedly hit by the enemy, whose batteries could be distinctly seen glistening in the edge of the woods a mile distant.

One round shot struck the wheel of a caisson, smashing it to atoms, and prostrating the “powder boy,” who was taking ammunition from it at the time. Had the missile gone ten inches further to the left, it must have exploded the caisson and caused fearful havoc among the Thirty-third. Here Colonel Taylor lay with his men for many long hours, exposed to the fury of the rebel cannoniers, without shelter or protection of any kind, until the after part of the day, when they were relieved by the Forty-third New York Col Baker and fell back to the second line of battle. …

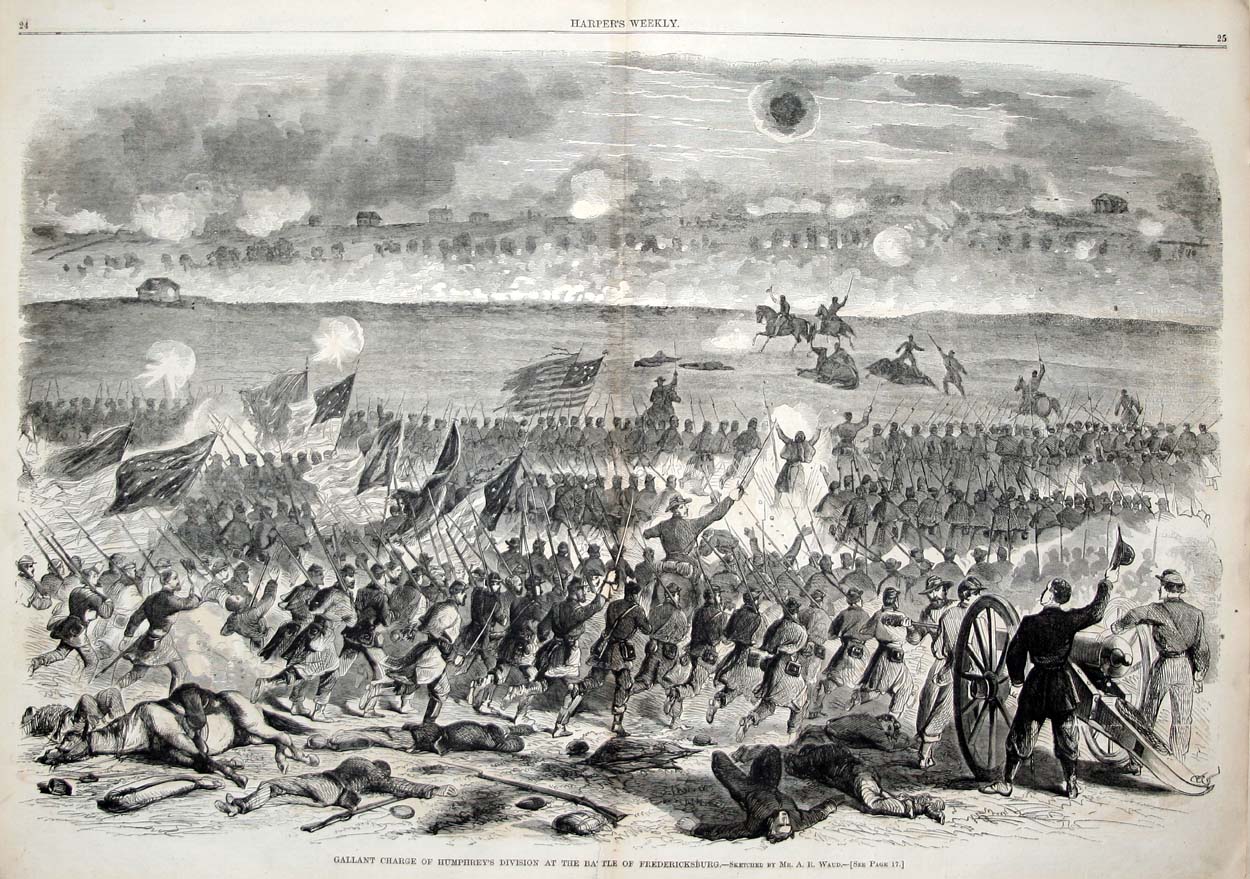

This image was published in the January 10, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly and is hosted at Son of the South. Hal Jespersen’s map at the top is licensed by Creative Commons.