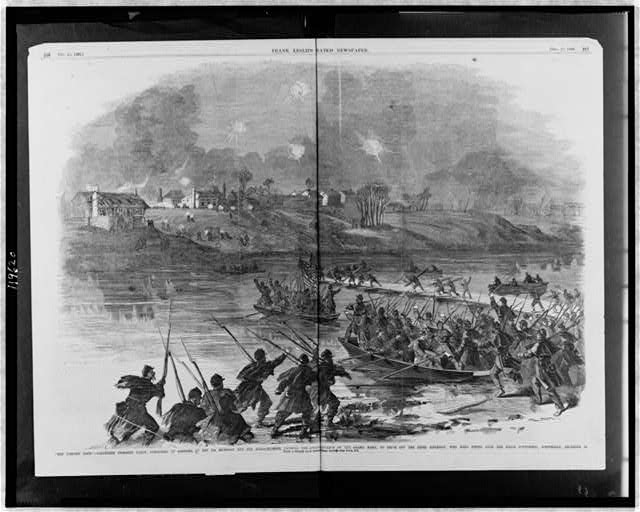

150 years ago today General Burnside’s Union Army of the Potomac tried to cross the Rappahannock to attack General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the vicinity of Fredericksburg. You can read a good account at Civil War Daily Gazette. Here’s a letter home from a member of the 50th New York Engineers, one of the regiments tasked with constructing the pontoon bridges.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in December 1862:

From S.W.E. VIELE.

CAMP AT FALMOUTH STATION, FREDERICKSBURG, Va.

Tuesday, Dec. 16, 1862.

DEAR PARENTS. – You have no doubt received my letter of last Thursday, and that told you that the battle of Fredericksburg had began. If you have not received that you have certainly heard of this battle through the papers. So considering all things I will write only the personal not the general particulars.

Last Wednesday morning myself and four others were ordered to move the hospital from White Oak Church to Falmouth Station; why, we knew not.

We did not go back to camp till nearly 12 o’clock that night, when we found all the boys gone with the pontoon boats, except a few left as guards, then we knew why we had moved the hospital to Falmouth, but little did we dream how soon it was to be used. – In the morning at 4 o’clock, we were aroused by the roar of cannon, and the continuous discharge of rifles. Soon the wounded and stragglers began to arrive in camp, when we received the news of our Captain’s death and other wounded. At that I sat down and wrote to you to let you know that I was all safe and sound as yet, and then started for the battle ground at Falmouth, distant 5 miles. Mother, you will say I did wrong in thus voluntarily exposing myself, but I could not stay at camp incurring risk, and think that my companions in arms were risking life and limb.

I first went to the hospital and saw my beloved Captain Perkins, and found that a ball had struck him in the side of the neck glancing down into the shoulder, killing him at once. He only said: “Boys take care of yourselves,” and died. his body has been sent home. Then I went to the bridge; there were six companies to lay three bridges. – Co.’s I,A,C,, and G, laid two bridges side by side. Co.’s K and F laid their bridge at the lower end of the town, while we laid our bridge at the upper end of the town, and the whole 15th reg.,, and a company of regular engineers managed to lay two bridges several miles below out of all danger. Our companies got their bridge half way across when a whole regiment of Sharpshooters opened fire on each bridge. The river here is about 20 rods wide, and the enemy were on a bank about as high as the American House hill. – The first round they fired was too low, and struck the water. The second volley went over their heads – this volley killed our Captain; then the order was given to fall back, which was obeyed with a will.

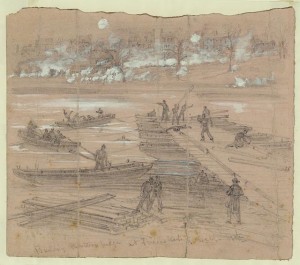

Nothing more was done until 2 P.M., when the artillery opened on the town, and such a continuous rain of shot and shell for over an hour, but few towns ever received. This drove most of the enemy beyond the town. The town lies very much like Waterloo, stretching along the river like the north half, and it is about the size of Geneva. – When the artillery quit firing, our boys volunteered to take some soldiers across in boats before beginning work on the bridge. Some of the 51st N.Y., and 7th Michigan volunteered to go. They went all safe until over half way across, when some Sharpshooters concealed in rifle pits fired on them, but nothing could stop those boys from crossing. Just as the boat touched the bank, they received another volley, killing the best man in Co. I, named Camplain; he was from Oswego. On seeing him fall, the boys charged up the bank on a run, firing as they went. Martin Mathews was one of the first to touch the other shore, and took the first prisoner taken in Fredericksburg. As soon as the others landed we went to work at the bridge and rushed it across “right smart;” then the troops crossed as fast as possible, and soon had possession of the town, the rebels falling back to their entrenchments on a hill behind the town. As soon as we had laid the bridge I went up into the town to see how things looked – and such a sight! dead Rebels lying in the street and houses, killed by the artillery, and you cannot imagine how they were cut and torn to pieces. I picked up a good English Enfield Rifle.

The loss of our Regiment was eight killed and 40 or 50 wounded, including Captain Perkins killed, Captain McDonaldwounded in the left arm quite badly, but will not lose his arm, and one other Captain wounded in the arm.

The whole loss on the Union side was 100 killed; the Rebel loss 1,000, that is, in laying the bridge; that was Thursday. Saturday the great battle of Fredericksburg was fought and Gen. Burnside fell back under cover of the town, and the night of the 15th his whole army recrossed the river.

The weather is warm daytime, and at night freezes a very little, but we have blankets enough to keep warm and comfortable.

Your son,

EDWARDS.

A New-York Times correspondent covered the events of the entire day. It’s a very thorough article; I’m just showing a bit of the beginning and the end.

From The New-York Times December 13, 1862:

THE OPERATIONS OF THURSDAY.; Fall Particulars from Our Special Correspondent.

FREDERICKSBURGH, Va., Thursday Night, Dec. 11.

I localize this letter Fredericksburgh, but it is assuredly “living” Fredericksburgh “no more.” A city soulless, rent by wrack of war, and shooting up in flames athwart night’s sky, is the pretty little antique spot by the Rappahannock, erewhite [erstwhile] the peculiar scene of dignified case and retirement. …

Although we are not yet fully informed of the present positions of the enemy, there seems to be good ground to claim that Gen. BURNSIDE has succeeded in outgeneraling and outwitting them. His decoys to make them believe that we were about to cross our main force at Port Conway, seem to have succeeded admirably. I suppose there is no harm now in my mentioning that among the ruses he employed was sending down, day before .yesterday, to Port Conway, three hundred wagons, and bringing them back by a different road, for the sole purpose of making the rebels believe that we were about to cross the river at that point. To the same end, workmen were busily employed in laying causeways for supposed pontoon bridges there, while the gunboats were held as bugaboos at the same place. Completely deceived by these feints, the main rebel force, including JACKSON’s command, seems to have been two or three days ago transferred twenty or twenty-five miles down the river. It must be remembered, however, that without the utmost celerity on our part they can readily retrieve this blunder by a forced march or two. Signal gun, at 6 o’clock this morning, gave them the cue to what was going on, and doubtless they have not been idle during the intervening hours. To-morrow will disclose what unseen moves have been made on the chess-board. W.S.

An editorial lauding the volunteers who drove the rebel snipers out of town from The New-York Times December 14, 1862:

HONORS TO HEROES.–

Every one who read the [???] account given by our Virginia correspondent, yesterday, of the unsurpassed coolness and valor displayed by the “forlorn hope” of 400 men, who crossed the Rappahannock in small boats, in face of the fire of the rebel sharpshooters, and drove them pellmell through Fredericksburgh, must have felt that these were heroes who, indeed, merited the recognition of their country. From the moment that the men of the Seventh Michigan sprang from their crouching places behind the rocks on the north bank of the river, and rushing for the pontoon boats, pushed them into the water, and leapt into them, all the time under the enemy’s fire — through that solemn scene when the first boat-load of gallant fellows pushed off amid the crack! crack! of a hundred rebel rifles, followed quickly by another and another boat-load, up to the moment when, rushing from their boats, amid the applauding shouts of our army which was watching them, they swept up the hill, on the further side of the river, and, musket in hand, fell upon the skulking rebels and killed, captured, or chased them all from their lurking places — everything through the whole affair was as fine as ever was anything in military history.

“It was,” said our correspondent, “an authentic piece of human heroism which moves men as nothing else can.” And as to its effect, he added: “The problem (of our army crossing the river) was now solved. This flash of bravery has done what scores of batteries and tons of metal had failed to accomplish. The country,” continued our correspondent, “will not forget that little band.” We hope the country will not forget them. Had these men been under NAPOLEON, their valor would have been signalized and honored on the spot; had they been in any European service, they would have received such token of recognition as would have filled them with pride for life, and been an heirloom for posterity; had they even been on the enemy’s side, they would have won the “cross” which the rebels give to their bravest. In our army, and on our side, we fear that all the recognition and reward these men will ever receive for their day’s service, will be to be kept waiting half a year or more for the forty cents they earned by it. It is a shame. If there can be no other reward, they certainly deserve the thanks of Congress as much as some of the big Generals who have received them. They would thus have their names enrolled on the national record as having at least deserved well of their country.

50th New York Engineers in Lead Story

![Street in Fredericksburg, Va., showing houses destroyed by bombardment in December, 1862 (photographed 1862, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-32890) Street in Fredericksburg, Va., showing houses destroyed by bombardment in December, 1862 (photographed 1862, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-32890)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/32890r-300x217.jpg)