A letter to Britain 150 years ago this week.[1]

To Sir Charles Lyell.

Boston, February 11, 1862

MY DEAR LYELL,-No doubt, I ought to have written to you before. But I have had no heart to write to my friends in Europe, since our troubles took their present form and proportions. …

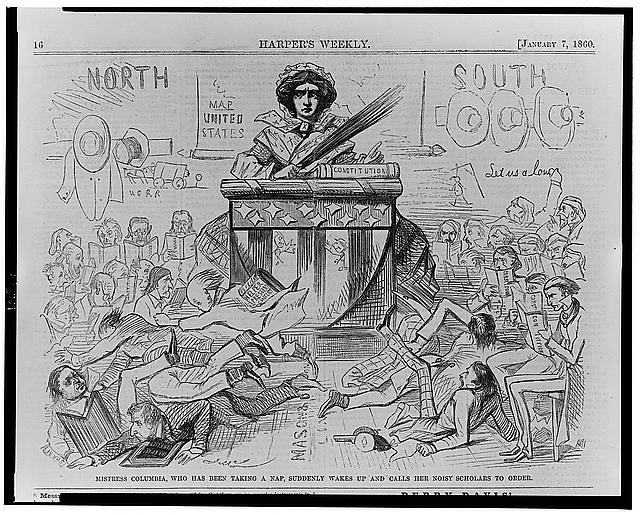

You know how I have always thought and felt about the slavery question. I was never an Abolitionist, in the American sense of the word, because I never have believed that any form of emancipation that has been proposed could reach the enormous difficulties of the case, and I am of the same mind now. Slavery is too monstrous an evil, as it exists in the United States, to be reached by the resources of legislation. … I have, therefore, always desired to treat the South with the greatest forbearance, not only because the present generation is not responsible for the curse that is laid upon it, but because I have felt that the longer the contest could be postponed, the better for us. I have hoped, too, that in the inevitable conflict with free labor, slavery would go to the wall. I remember writing to you in this sense, more than twenty years ago, and the results thus far have confirmed the hopes I then entertained. The slavery of the South has made the South poor. The free labor of the North has made us rich and strong.

But all such hopes and thoughts were changed by the violent and unjustifiable secession, a year ago; and, since the firing of the first gun on Fort Sumter, we have had, in fact, no choice. We must fight it out. Of the results I have never doubted. We shall beat the South. But what after that? I do not see. It has pleased God that, whether we are to be two nations, or one, we should live on the same continent side by side, with no strong natural barriers to keep us asunder; but now separated by hatreds which grow more insane and intense every month, and which generations will hardly extinguish. …

You can read more of this letter at Google Books starting on page 446.

Free labor might have been leaving slavery in its dust, but that apparently wasn’t affecting planters – and slavery was an ingrained southern institution. There was never a national consensus on the need for a reasonable emancipation.

George Ticknor was born in Boston and died in Boston, but he traveled throughout Europe, was a Harvard professor, and helped establish the Boston Public Library. He was known for his history of Spanish literature.

Scottish-born Charles Lyell was the foremost geologist of his time.

- [1]Henry Steele Commager and Erik Bruun,eds.,The Civil War Archive. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal,2000. pp. 354-355.↩