In yesterday’s post a Richmond Dispatch correspondent made the case for the CSA’s officer class to be concerned about the condition of the common soldier during the winter months. As Civil War Daily Gazette is reporting Stonewall Jackson’s troops suffered in the ice and wind as they marched south from the Potomac, after having failed to take Hancock, Maryland. The 19th New York was one of the regiments in the brigade General Banks sent to belatedly reinforce Hancock. The 19th has had a rocky time since volunteering in April, including mass desertions in the fall. The remaining troops are quite happy about their imminent conversion to artillery. But here they can still suffer as infantry on the three day march from Frederick to Hancock.

Henry Hall writes about 11 years after the events. From Cayuga in the Field (p 86-87):

Although the rebels remained quiet on the upper Potomac, they were gathering there in large force. It was deemed expedient to strengthen the Federal lines there, and Gen. Banks ordered the 3d brigade to proceed to Hancock for this purpose. Preparing two days’ rations, the brigade marched at 5 a. m. on January 6th, the 28th New York in advance, with the 5th Connecticut, 46th Pennsylvania, and 19th New York following in the order named, which was their regular order in the brigade. Camp was left standing by the 19th, for owing to the ice and snow tents could not be struck. Company F stayed to pack up and bring on the baggage. The sick were left under care of Dr. McClellan, of the 5th Connecticut. The brigade, being temporarily under the command of Col. Donnelly, of the 28th New York, made a headlong march, through snow four inches deep, over mountain ranges and rough roads to Hagerstown, The 19th, nearly starved, without sufficient rations, was, by Donnelly’s orders, kept out in the open country that night, to bivouac and freeze in the snow, sleeping by fences, in straw stacks, and some few in barns, while the other regiments were housed and fed in the village. The next day Gen. Williams overtook the command while plodding through the snow on another forced march of twenty-six miles, and at once halted it at Clear Spring, a good Union village, on the bank of the Potomac, after giving Donnelly a thorough talking to for his disgraceful treatment of the 19th. On this day’s march the men were so hungry, from failure of the commissary to supply them with rations, that Lieut.-Col. Stewart stopped a commissary wagon on the road and issued a barrel of crackers to each company, for which they were very grateful. How nice Elmira hash would have been then! At Clear Spring, churches, school houses and inns were occupied for the night. Next day the march was pushed at a rapid pace, in sight of the Potomac all day, a small force of the enemy following on the other side. Lest the confederates should open fire on the brigade with shell, it marched in open order. The 19th, being indifferently supplied with shoes, straggled somewhat on the home stretch to Hancock, but a strong rearguard prevented straying away. On a former march of the regiment — from Pleasant Valley to Hyattstown — the Surgeon obtained some one horse, two-wheeled ambulances, as traps for feigners of sickness and those shamming to be disabled. They were so hung that while going down hill the occupants would stand on their heads; going up, on their feet. The most inveterate shammer generally had his fill of false pretenses after one day’s ride in one of those “cussed machines,” and never gave out on the march so quick after that if he could help it Either its memory, or the now superior discipline of the regiment made them on this march entirely unnecessary.

The brigade entered Hancock, a little, ancient, one-horse village on the bank of the Potomac, at a point where Maryland is only three miles wide, reaching it at 3 P. M. Public buildings were assigned to the 19th, and that night the regiment nursed its frozen feet and hands in comfortable quarters.

You can see a Harper’s Weekly report on Hancock (in warmer weather) at Son of the South. The 19th would have appreciated that alcohol that was being dumped in one of the images.

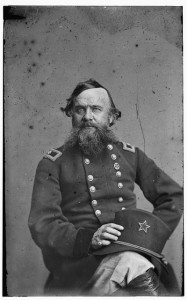

A native of the Nutmeg State, Alpheus Starkey Williams moved to Detroit in 1836. He worked at a bunch of different careers:

He was elected probate judge of Wayne County, Michigan; in 1842, president of the Bank of St. Clair; in 1843, the owner and editor of the Detroit Advertiser daily newspaper; from 1849 to 1853, postmaster of Detroit.

When Williams arrived in Detroit in 1836, he joined a company in the Michigan Militia and maintained a connection to the military activities of the city for years. In 1847, he was appointed lieutenant of a regiment destined for the Mexican-American War, but it arrived too late to see any action. He also served as the president of the state’s military board and in 1859 was a major in the Detroit Light Guard.

Williams was active as a general throughout the Civil War. At The Alpheus Williams Website you can read a letter in which Williams describes the brutal conditions at Hancock.

Pingback: Fire as Cold Comfort | Blue Gray Review

Pingback: Killing Themselves Warmly | Blue Gray Review