From the Richmond Daily Dispatch November 26, 1861:

A salt Stampede and its Finale.

The Augusta (Ga.) Sentinel, of the 23d inst., says:

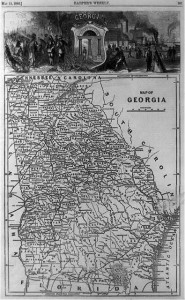

Upon the reception of the news that Governor Brown was appropriating salt at other points, the article became exceedingly active in this market. A multitude of drays were engaged in transporting salt to the other side of the Savannah. Somehow Governor B. got an inkling of the movement and gave orders, by a dispatch, to our city authorities, that all the salt in the city in the hands of dealers should be seized. Accordingly, over 700 sacks were sized [seized?] yesterday at the depot of the South Carolina railroad. Much had, however, made its escape to South Carolina, out of reach of the Gubernatorial talons.

Here’s the governor’s salt proclamation reproduced in the same issue of the Daily Dispatch:

Seizure of salt by the Governor of Georgia.

We have already noticed the fact that the Governor of Georgia had issued a proclamation directing the seizure of salt in that State, to be paid for at fair rates. The following is the proclamation alluded to:

Executive Department,

Milledgeville, Ga., Nov. 18th, 1861.

Col. Jared I. Whitaker, Commissary General, &c.,Colonel:

I have learned that there is now a considerable quantity of salt in the depot of the Central Railroad at Savannah, and I have notified Mr. Adams, the Superintendent of the road, that he is required to detain it in the depot subject to your order, for the use of the army. You are hereby instructed to take charge of the salt, and give Mr. Adams your receipt for it. When the owners present their claims you will pay each five dollars per sack, which I consider just compensation. As we shall need a very considerable quantity for public use, you will inform me of any which you may find in the hands of speculators of traders who are selling at more than five dollars per sack with freights from Savannah added, and I will give you directions as to the seizures necessary to be made. No seizures will be made of any supplies in the hands of persons who are selling to the people at five dollars per sack with [fr]eights from Savannah added. I feel that it is gross injustice to the Government and to the people to permit speculators who have managed to get the control of articles of absolute necessity, to sell them at the enormous prices now demanded in the market.

The Constitution of this State clearly provides that private property may be taken for public, use by paying just compensation. Under this provision, I feel it my duty when any necessary article is controlled by a few persons, who demand from the State and her citizens unreasonable and unjust compensation for it, to authorize you to seize in the hands of those who ask the highest prices such supplies as may be needed for public use, and pay the owners just compensation.

I very much regret the necessity which must control my action in the present emergency, but a sense of duty compels me to assume the responsibility. If the constituted authorities do not interfere, but will pay on the part of the State the high prices demanded by unpatriotic speculators, the cost of the supplies necessary to maintain our army will soon swell the public debt to an enormous burden, and as the high prices paid by the State will control the markets and compel its citizens to pay as much, provisions will be placed out of the reach of the poor who labor for their daily bread, and much suffering and misery must be the result.

I shall use all the power vested in me by the Constitution and laws of this State to prevent these deplorable results.

Very respectfully, &c.,

Joseph E. Brown.

You can read more about Brown at The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Joseph E.Brown was actually born in Pickens, South Carolina. As governor Brown supported secession after Lincoln’s election, but opposed the increasing power of the central Confederate government:

As soon as the Confederate States of America was established, Brown spoke out against expansion of the Confederate central government’s powers. He denounced Davis in particular. Brown even tried to stop Colonel Francis Bartow from taking Georgia troops out of the state to the First Battle of Bull Run. He objected strenuously to military conscription by the Confederacy. After the loss of Atlanta, Brown withdrew the state’s militia from the Confederate forces to harvest crops for the state and the army.

But he obviously didn’t mind using state power to control the price of a major necessity. If the state paid the speculators’ price, government debt would be pushed up and poor people would be driven out of the market.

Salt in the American Civil War was important for its ability to preserve food and its role in curing leather. This Wikipedia article gives details about the way Georgia controlled the salt price.

In Georgia, the price of salt depended on one’s family circumstances. Heads of families could purchase a half-bushel of salt for $2.50. If a widow had a son in the Confederate army, the price was only $1.00. But if the widow’s husband served his nation, the price was free. Local court clerks sent the salt requests to the state government, which in turn allotted the salt to the counties as requested.