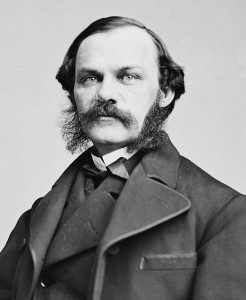

If I had put down my TWO CENTS for a copy of The New-York Times 150 years ago today, I could have read a dispatch from a reporter with General McDowell’s Union army at Fairfax Court House. I’m assuming H.J.R., the editorial correspondent, is Henry Jarvis Raymond, the founder and editor of The Times. The star of the newspaper is reporting from the front.

From The New-York Times July 20, 1861:

FROM GEN. McDOWELL’S ARMY.; The Halt at Fairfax–Movements of the Troops– Incidents–Haste of the Rebels.

Editorial Correspondence of the New-York Times.

FAIRFAX COURT HOUSE, Va., Wednesday Night, July 17, 1861.

The General decided not to move forward any further to-night, mainly because the troops had been so fatigued by their day’s march as to render any further movement unadvisable. …

Everything we see here shows that the rebels left the place in the greatest imaginable haste. …

But the strongest evidence of haste was found in the abandoned camps. In that of the Palmetto Guards, lying nearest the side of the village at which our troops entered, almost everything remained untouched. The uniforms of the officers, plates, cans, dishes and camp equipage of every kind, an immense quantity of excellent bacon, blankets, overcoats, &c., &c., were left behind, and the tables of the officers, spread for breakfast, remained untouched. In a vest pocket of one of the officers was found a gold watch; — in another was a roll of ten cent pieces amounting to ten dollars; — letters, papers, books, and everything collected in a camp which had been occupied for some days, were abandoned without the slightest attempt to take them away. In another camp in a field at the extremity of the town, occupied by another South Carolina regiment, the same evidences of extreme haste were visible. Unopened bales of blankets were found; scarcely any of the utensils of the camp had been removed, and bags of flour and flitches of bacon were scattered over the ground. …

The discovery of these abandoned camps afforded a splendid opportunity for our troops to replenish their slender stock of camp furniture. They rushed to the plunder with a degree of enthusiasm which I only hope will be equaled when they come to fight. Men were seen crossing the fields in every direction loaded with booty of every description, — some with tents, some with blankets, over-coats, tin pans, gridirons, — everything which the most fastidious soldier could desire. I am sorry to say that they did not limit their predatory exploits to these camps, which might, perhaps, be considered fair objects of plunder. The appetite once excited became ungovernable, — and from camps they proceeded to houses, and from plunder to wanton destruction. Five or six houses were set on fire, others were completely sacked — the furniture stolen, the windows smashed and books and papers scattered to the winds. Presently in came soldiers bringing chickens, turkeys, pigs, &c., swung upon their bayonets, — proud of their exploits and exultant over the luxurious and unwonted feast in immediate prospect. These depredations were far too numerous for the credit of our troops, — and I was glad to see, as I passed the General’s head-quarters, half a dozen of the offenders under arrest and in a fair way of receiving the punishment which they deserve.

This matter of plunder, however, it is humiliating to confess, is more or less inseparable from war. It is not possible, when 30,000 or 40,000 men are marching through an enemy’s country, to prevent them from supplying their necessities and gratifying their lawless propensities by depredations upon the foe. The English understand this, and, as a matter of necessity, permit it. A good deal of this, in the case of our troops, is due to the spirit of frolic, which characterizes their progress thus far in this war. They act as if the whole expedition was a gigantic pic-nic excursion. After we were fairly in town, to-day, two of the troops dressed themselves in women’s clothes and promenaded the town amid the shouts and not over-delicate attentions of the surrounding troops. Others paraded the streets under the shade of tattered umbrellas which they had found in camp, — and one, donning a gown and broad bands, marched solemnly down the principal street, with an open book before him, reading the funeral service of “that secession scoundrel, JEFF. DAVIS.” All these humors of the camp help to pass the time, — and are pursued with just as much reckless abandon, now that they are on the eve of a battle which may send half of them into eternity, as if they were simply on a holiday excursion. Perhaps it is well that they do not take the matter any more seriously to heart, — for it is one which will scarcely bear very serious reflection.

The men are in capital spirits, and are quite ready for the approaching crisis. The best attainable information leads us to believe that the enemy is quite as strong as we are at Manassas, and that they have the advantage of intrenchments, constructed carefully and at leisure under the immediate supervision of Gen. BEAUREGARD, and the additional advantage of rapid railroad communication with Richmond and their base of operations. It is said here that Gen. B. informed the troops here last night that, whether they contested possession of this place or not, the question of an independent Southern Confederacy would be decided at Manassas, — and that he made each man of them take an oath to right to the last man. If we had not heard a good deal of this before, and seen these oaths followed by swift retreats, we might attach more importance to them. According to present appearances, however, I am inclined to think that the rebels will dispute Manassas with whatever of force and vigor they possess; and it is not impossible that Gen. MCDOWELL may deem it advisable to await reinforcements, if, after reconnoitering it he finds the place as formidable as he anticipates.

The troops are bivouacked to-night in the fields and under the open sky. The General and Staff, like the men, sleep on the ground, rolled in their blankets, and I found the General at three o’clock taking his dinner of bread and cheese, with a slice of ham, on the top of an overturned candle-box by the side of the main highway. When it comes to sleeping I rejoice that I am a civilian, for I am much better cared for to-night than the Commander of this, the largest force ever marshaled under one General on this continent. There are two hotels in this place, — both evidently feeble at their best estate, and just now, after a prolonged visit of rapacious and boisterous rebels, in a state of suspended animation.

Capt. RAWLINGS, of the New-Hampshire Regiment, with that versatility which enables a New-Englander to turn from commanding armies to keeping a hotel with marvelous facility, has succeeded in infusing into the mind of the invalid widow who keeps one of them, that the National troops have not come to sweep her and hers from the face of the earth. She has accordingly provided me with a bed, which, if not luxurious, is, to my untutored mind, decidedly preferable to one on the ground, even under the brilliant sky and softly superb moon of this July night.

H.J.R.

I think the whole article is a great read, and I especially like Raymond’s forboding sense that the pic-nic atmosphere is going to change soon with the “approaching crisis” – unless General McDowell decides to wait for reinforcements. Of course, that did not happen.

Pingback: A Spy? Without a Country? | Blue Gray Review