The last we heard from the 19th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment they had moved from drill camp in the District of Columbia to Martinsburg in current West Virginia. They arrived on July 8th. Their purpose was to bolster General Patterson’s army for its expected movement against the Confederate forces in the Winchester area. As Cayuga in the Field (by Henry Hall and James Hall) points out, a few noteworthy events occurred during the week in Martinsburg.

When Patterson found out that the the 19th was attired in gray he sent white cloth strips to be worn as armbands to help distinguish the 19th from the rebel army. Henry Hall says that many of these armbands were “lost” the next day – maybe because white is the color of surrender, maybe because the white rags made the 19th’s shabby gray uniforms look even more ridiculous. My thought was it might help prevent some ‘friendly’ fire.

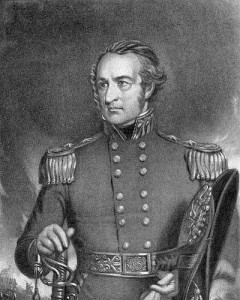

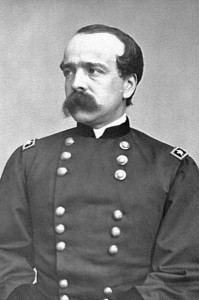

The 19th became part of the 8th Brigade commanded by Colonel Daniel Butterfield. General Charles W. Sandford led the division the 19th was part of.

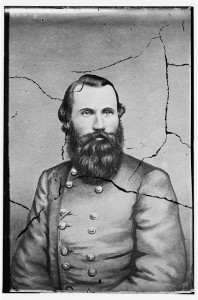

While out foraging a couple members of the regiment got into a fracas with a squad from Jeb “Stewart’s” cavalry. Both were captured; one died from his wounds; the other spent time in prisons in Richmond (Libby), Tuscaloosa, and Salisbury, N.C. He was exchanged in June 1862.

The 19th’s leader, Colonel Clark was relieved from command and put under arrest by General Patterson. Most of the captains and lieutenants in the regiment objected to Clark’s management style and told Patterson about it. Lieutenant-Colonel Clarence A. Seward took command, while Clark stayed with the regiment, always riding in its rear, until he was eventually exonerated.

The 19th marched with the rest of Patterson’s army from Martinsburg to Bunker Hill on July 15, 1861. They had to take some razzing from splendidly equipped soldiers from Massachusetts about the 19th’s shabby gray duds. One member of the 19th tried to joke about it a bit by saying that “it was a regiment of convicts from Auburn, let out of prison on condition that they would serve.” The Auburn Correctional Facility began operation in 1816.

On approaching Bunker Hill, at night fall, the sound of firing floated in from the advance. The rebel Stewart, with 600 cavalry, was preparing to dispute the road with our leading regiments, when the Rhode Island battery taught them a lesson and sent the flying in disorder. The firing electrified the Federals, whose long, dark columns of men pushed forward in haste, but the fight was over before any could come up.

The 19th got to camp in a just-cut wheatfield – the sheaves softened the ground for the soldiers who had no tents because the wagons were far behind. Despite orders to the contrary the 19th ate off the people of Bunker Hill:

It was contrary to the stringent orders of the tender-hearted Patterson to forage upon the inhabitants of the Valley. A great deal of it took place, notwithstanding. The army believed in the maxim of subsisting on the enemy. Undoubtedly, however, high military reasons existed for putting the practice under peremptory ban. A month before, Beauregard had, in a blatant proclamation, asserted that the South was invaded for ravage, for “beauty and booty,” as he expressed it. It became desirable, at this stage of the war, to convince the South of the untruth of the assertion. Hence Patterson imperatively forbade foraging in his army, and tried to stop it. Lieut. Col. Seward’s very first order, issued on arriving at Bunker Hill, was on this subject. Said that document: “The object of the journey of the Army of the North is to protect the property of the United States, not to plunder the property of citizens.”

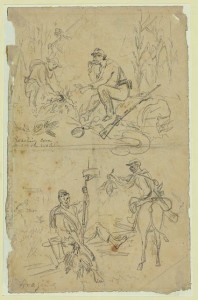

But when the Cayuga men stacked arms on the afternoon of the 15th of July, and broke ranks for supper, there was that pressing on their attention, which then was of far greater present importance to them than the ease and convenience of Virginia rebels. They were hungry and almost supperless. Their commissary only afforded a scant allowance of hard-tack and salt pork, and the gnawings of empty stomachs prompted them to cast their eyes upon the forbidden poultry and cattle with which the farms all around swarmed. The temptation was irresistible. On various excuses, with permits and without, the men managed to send out foragers — jayhawkers, as they were then and thereafter called — and there was a general ransacking of the neighborhood for fresh provisions. Chickens, turkeys, several sheep, cows and calves, and other domestic game, soon found their way into camp. Not only that night, but the following day, the 19th New York feasted on the fat of the land. Jayhawkery, once begun, took in other things than provisions. Some of the men caught horses, and made the field roar with their frantic and ridiculous equestrianism, while an old lady’s wardrobe was made to do scarecrow duty on the facetious but scandalous volunteers. One fellow seized on a quantity of what he supposed to be flour, to regale his mess with pancakes and gravy for a turkey stew. To his speechless astonishment, on seeing his pancakes stiffen and his gravy refuse to run, he found his treasured bag of flour to be plaster of Paris.

Foraging was common in all the Federal regiments. Yet Patterson, who bore ill will toward the regiment of Col. Clark, searched the camps and had several tons of dressed mutton, veal, hams, and other foraged provisions, brought in army wagons to the camp of the 19th and there buried, to affix a reputation for javhawking, especially on that regiment. The event is of historical importance, as Patterson afterwards gave, as one of the reasons why he did not attack Johnston, that his commmand was short of provisions and could not get up his supplies and attack Johnston too.

No booty, indeed. This story affects me, but it seems way too complicated to start moralizing. Henry Hall is writing twelve years after the events he’s justifying.

was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel of Virginia Infantry in the Confederate Army on May 10, 1861. Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee, now commanding the armed forces of Virginia, ordered him to report to Colonel Thomas J. Jackson at Harper’s Ferry. Jackson chose to ignore Stuart’s infantry designation and assigned him on July 4 to command all the cavalry companies of the Army of the Shenandoah, organized as the 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment. He was promoted to colonel on July 16.

Butterfield was active throughout the war and is credited with writing “Taps”.

![Bummers [Foragers] Bummers [Foragers]](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/21787r-300x219.jpg)

Pingback: Souvenirs | Blue Gray Review