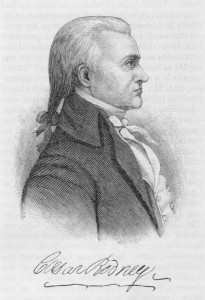

235 years ago today Delaware’s Caesar Rodney wrote to his younger bother, Thomas:

Philadelphia, July the 4th, 1776

Sir:

I arrived in Congress (tho detained by thunder and rain) time enough to give my voice in the matter of Independence. It is determined by the Thirteen United Colonies, without even one decenting Colony. We have now got through with the whole of the declaration, and ordered it to be printed, so that you will soon have the pleasure of seeing it. Hand-bills of it will be printed, and sent to the armies, cities, county towns, etc. To be published or rather proclaimed in form. Don’t neglect to attend closely and carefully to my harvest and you’l oblige Yours, etc.

CAESAR RODNEY

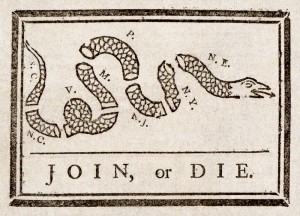

All the colonies apparently agreed with Ben Franklin that if they were going to secure their Independence and enjoy a greater Liberty they were going to have to unite. Thankfully, there was dissent throughout the years, but the idea of Liberty depending on the federal Union always carried the day. Of course, that all changed in late 1860 when South Carolina and other southern states opted for disunion. By 150 years ago today there were eleven states in a new Southern Union:

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch July 4, 1861:

Fourth of July.

This national anniversary will pass by under circumstances novel and strange. It cannot be celebrated in the usual style. The condition of the country does not admit of that. We have a war, in which the very people who asserted their independence on this day, eighty-five years ago, are struggling, the one for the maintenance of the principles of that independence, the other for crushing them to death. The day is still to us a day memorable for the assertion of principles we revere, and mean to defend with our lives and the last drop of our blood, while to them it should be a day of mourning for the liberties which it proclaimed, but which they have lost, probably forever, in order to force the yoke of tyranny upon the South.

It is to be regretted that one of the incidents of the present struggle is the inability of our people to celebrate this day according to usage — indeed it would be inappropriate at such a time to undertake to observe it in that manner. But it is a sufficient tribute to it that we are engaged in the maintenance of the principles of human rights and liberty it announced, and that we are ready to sacrifice our lives and all we have in the effort. Could the departed sages of ’76 behold the scenes of today, they could desire no better evidence of devotion to their acts and principles than is displayed by the people of the South. Today, when the North meets in Congress to approve tyranny, to sanction usurpation, and sustain a war of oppression and desolation, we are at our guns ready to resist that war, and to triumph or perish in the struggle for the principles of the unanimous declaration of the immortal Congress of 4th July, 1776.

It was a great day for a (military) parade in Washington D.C. From Cayuga in the Field by Henry Hall and James Hall:

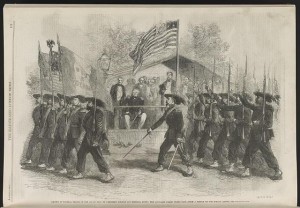

Fourth of July was celebrated in and around Washington joyously. The grand feature of the day was the review of the New York troops, then under the command of Gen. Sandford, who had obtained permission to receive a marching salute from the twenty-three regiments of his division and had issued orders accordingly.

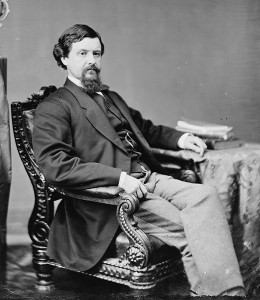

July 4, 1861: Garibaldi Guard before "men who held the destinies of America in their hands" (LOC - LC-DIG-ppmsca-31563)

At 7 A. M., the 19th, with full canteens, fell into line, and marched to Washington. Regiments simultaneously pressed in from every direction, their rifle barrels flashing in the bright sunlight and colors proudly floating on the morning air. All gathered on the great Pennsylvania Avenue leading up to the Executive Mansion and formed into a column of great length. Other shoddy uniforms were there, besides those of the 19th, that day, and Gen. Sandford had the rare privilege of calling the attention of the men who held the destinies of America in their hands, to the manner in which the opulent commonwealth of New York clad her volunteers. Near the White House, stood a beautiful pavilion, sheltering from the overpowering heat of the sun, the President and his family, Gen. Scott, Secretaries Seward, Cameron and Smith, Gens. Dix, Mansfield, Sandford, and other high dignitaries and commanders. Past this point, the column was finally put in motion. It was an hour and a half in passing.

The 19th marched, in its proper place in column, from Connecticut Avenue to 6th street, and then turned off and returned to camp, devoting the rest of the day to high festivity. In the evening, the officers of the regiment collected, by invitation, in the street of Company B, which was decorated with greens for the occasion, where they spent the evening in speech-making and feasting. Speeches were made by Col. Clark, Lieut.-Col. Seward, Capt. Kennedy, Capt. Stephens, Hon. Theo. M. Pomeroy, M. C, and others. Fireworks and bonfires illuminated the scene, and the band of Col. Ernstein’s Philadelphia regiment was present with inspiring music. Some of the men engaged in dancing, and there were games and general merriment and hilarity throughout the camp.

Notes

1) Henry Hall remembered the Fourth in Washington as much more joyous than the Richmond editorial is making it seem for the Southern Union. It seems a much more somber tone than the scene from Savannah in November 1860.

2) I got the Caesar Rodney letter from The Spirit of Seventy-Six edited by Henry Steele Commager and Richard B.Morris, New York 1967, which they got from Edmund C. Burnett, ed., Letters of Members of the Continental Congress, Washington D.C., 1921-1936. Commager and Morris mention that New York abstained in the vote for the Declaration, but 4 of 5 members of the New York delegation signed it. By 1861 New York’s troops were in full march for the Washington dignitaries.

3) Thanks to Seven Score and Ten for listing the Richmond Daily Dispatch as a link and to the University of Richmond for hosting it.

4) People sure seemed to enjoy the giving and receiving of speeches in the 1800’s. Theodore Medad Pomeroy was a Republican Congressman from Cayuga County, New York.

5) To be honest, the first thing I thought of when I saw that painting of the Signing was the Third Reich.

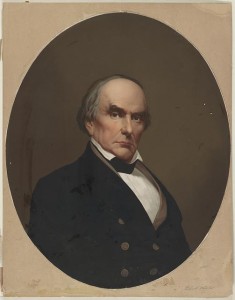

6) Caesar Rodney made it just in time to Philadelphia (from Wikipedia link):

Meanwhile, Rodney served in the Continental Congress along with Thomas McKean and George Read from 1774 through 1776. Rodney was in Dover attending to Loyalist activity in Sussex County when he received word from Thomas McKean that he and George Read were deadlocked on the vote for independence. To break that deadlock, Rodney rode eighty miles through a thunderstorm on the night of July 1, 1776, dramatically arriving in Philadelphia “in his boots and spurs” on July 2, just as the voting was beginning. At least part of Rodney’s famous ride was probably made in a carriage. He voted with McKean and thereby allowed Delaware to join eleven other states in voting in favor of the resolution of independence. The wording of the Declaration of Independence was approved two days later, and Rodney signed the famous parchment copy on August 2. A conservative backlash in Delaware led to Rodney’s electoral defeat in Kent County for a seat in the upcoming Delaware Constitutional Convention and the new Delaware General Assembly.

7) Thomas Rodney would move South. In 1803

President Jefferson appointed him as the chief justice for the Mississippi Territory. He bought land in what was then Jefferson County, Mississippi and moved to Natchez to assume his new duties as the senior federal judge for the Mississippi Territory from 1803 to 1811.

Pingback: Mutineers Stopped At Long Bridge | Blue Gray Review