Conflict in Texas

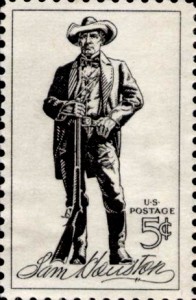

On February 1, 1861 the Texas secession convention voted to secede. On February 23 Texas citizens voted to ratify the secession decision. The Texas secession convention has already sent representatives to the new Confederate government in Montgomery. However, Governor Sam Houston is still resisting the idea of Texas joining the Confederacy. Here’s an article from the March 14th issue of The New-York Times (The New York Times Archive):

IMPORTANT FROM TEXAS.; GOVERNOR HOUSTON AT ISSUE WITH THE SECEDERS.

GALVESTON, Texas, Monday, March 11.

Gov. HOUSTON has refused to recognize the Convention. He considers that its functions terminated in submitting the Secession Ordinance to the people. He tells the Convention that he and the Legislature (which meets on the 18th,) will attend to the public questions now arising; and he favors a new Convention to make such changes in the State Constitution as may be necessary. He opposes Texas joining the Southern Confederacy.

The Convention, in reply, passed an ordinance, claiming full powers, promising to consummate, as speedily as possible, the connection of Texas with the Confederate States, and notifying the State of this course. The Constitution will at once require all officers to take the oath of allegiance to the support of the new Government, and carry out the Convention ordinances.

It is reported that Mr. CLARK will be put in Mr. HOUSTON’S place, if the latter refuses the oath; also that Gov. HOUSTON is raising troops on his own account.

One thousand five hundred Texan troops are at and near Brownsville.

______________________

Conciliation Toward Mexico

From The New-York Times March 13, 1861 (The New York Times Archive):

THE NEW MINISTER TO MEXICO

Among several nominations sent to the Senate yesterday, that of THOMAS CORWIN, as Minister to Mexico, will be accepted by the country with singular approbation. Mr. WELLER, the latest of Mr. BUCHANAN’S appointees, upon that mission, has involved himself in unpleasant relations with the Liberal Government, at a moment of all others when it is important to secure with it the best feeling and the largest influence. Especially important is it to place in communication with them a person who shall be able and faithful to counteract the schemes of secession — schemes, which are likely to compass at once the deglutition of the prey so long and hungrily coveted. Mr. CORWIN, as an earnest opponent of the Mexican war, will be likely to meet with a very different reception from that he awarded the American invaders; in fact, he will immediately exert an influence with the Government, which will greatly strengthen it to resist not only the advance of secession, but the unfriendly and untimely pressure of the European Powers. He will, of course, be confirmed.

Thomas Corwin was a wagon boy for General William Henry Harrison during the War of 1812. He had a long political career, including stints as Ohio governor and Secretary of the Treasury during the Fillmore administration. From Wikipedia:

In 1860, he was chairman of the House “Committee of Thirty-three,” consisting of one member from each state, and appointed to consider the condition of the nation and, if possible, to devise some scheme for reconciling the North and the South.

He resigned only a few days into the 37th Congress after being appointed by the newly inaugurated President Abraham Lincoln to become Minister to Mexico, where he served until 1864. Corwin, well-regarded among the Mexican public for his opposition to the Mexican-American War while in the Senate, helped keep relations with the Mexicans friendly throughout the course of the Civil War, despite Confederate efforts to sway their allegiances.

Corwin’s appointment as Ambassador to Mexico seems to have been a good decision by the Lincoln administration.

_________________________________

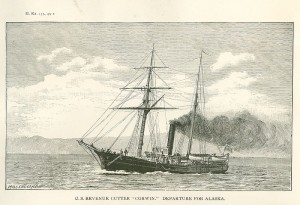

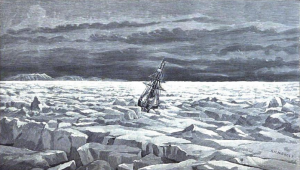

The Thomas Corwin sailed on most of its missions to the vicinity of Alaska and the Bering Sea.