150 years ago today President-elect Abraham Lincoln was already in Buffalo, New York enjoying a sabbath day rest (Civil War Daily Gazette). On February 18, 1861 The New-York Times published a report by HOWARD, its Special Correspondent detailing Lincoln’s trip from Cincinnati to Columbus on February 13th. Here’s some excerpts:

The Trip from Cincinnati to Columbus Incidents and Accidents on the Way Arrival and Scenes at the Capital of Ohio Speeches Dinner How the Trip affects Him.

From Our Special Correspondent.

AMERICAN HOUSE

COLUMBUS, Ohio, Wednesday, Feb. 13, 1861. …

The departure from Cincinnati this morning was accompanied with very little ceremony. At a few moments before 9 o’clock, Mr. LINCOLN, with his family, drove to the depot, where there were gathered a great many people, who were desirous of catching one more glimpse of his peculiar physiognomy. As he stood on the platform, with his head bared, I was startled by the careworn, anxious look he wore. His forehead and face are actually seamed with deep-set furrows and wrinkles, such as no man of his years should have. For his own sake, it is to be regretted that this excursion is being made. His original plan, which was to proceed directly and quietly to Washington, was much better, and it was with great reluctance that he acceded to the desires of his friends, who are now thoughtlessly and foolishly wearying him, and wearing the life out of him by inches. When receiving his friends, shaking them by the hand, and excited by conversation, his eye is light, and his countenance cheerful, but when standing, as he frequently does upon the rear platform of his car, listening to a prosy address, or shuddering at the brazen efforts of some country band, his eye is dull, his complexion dark, his mouth compressed and his whole appearance indicates excessive weariness, listlessness and indifference. As he goes from place to place, local dignitaries, petty officials, and patriotic committees decked with ribbons, rosettes and badges poster and bore him, while the populace, regardless of decency, and thoughtful only for their self-gratification continually do cry, “Hurrah for Old Abe,” “Let’s grab his hand, “Bully for you,” and “Go it old horse.” No one can for a moment mistake the animus of all this parade and fussation. It is evidently an honest and sincere desire on the part of the people and the people’s representatives, to show their future President all the honorable attention in their power; to surround him with tried and trustworthy friends, and to assure him of their love and admiration, their support and sympathy. As such, Mr. LINCOLN submits with pleasure to the infliction, but it is a terrible ordeal through which to pass, when bound as he is not to a place of rest and easeful quiet, but to a scene of discord, trouble and possible danger.

Traveling, as does the Presidential party, only in the day-time, is not very fatiguing in itself considered, but when one is obliged to pop up at every station, go upon the platform, hear a tedious speech, make a pertinent answer, smile, bow, be pleased and eminently gratified, it’s quite, another affair. To-day, on the trip hither from Cincinnati, we made half-a-dozen stoppages. The principal ones were Morrow, Xenia and London, at all of which there were immense concourses of people, all anxious to see and hear the form and voice of the President elect. At Xenia they were really crazy. They jumped upon the car-roof, climbed in at the windows, attempted to force the doors and storm the platform. It was about 1 o’clock when we reached that point, and as we had breakfasted quite early in the morning, the anticipated and promised lunch was regarded most favorably by the several eyes of faith, and the various unemployed digesting apparatuses that float and uncomfortably moved from car to car most restlessly. Imagine the feelings of the President elect, of all the corporals, of the high and mighties, of the four reporters and the untitled hangers-on, when it was announced by the Chairman of the gastronomic department that a lunch, varied and extensive in its dainties, had been prepared, had been left on the table in the depot, and had been devoured by the voracious and Democratic crowd, who now, with well-filled paunches, with broad and buttery hands, and with the most comfortable abdominal sensations, were clamoring for a third speech from their dear old Rail-Splitter. Mr. ROBERT T. LINCOLN, familiarly styled, in the Herald correspondence. “Bob,” as he also is by all who are intimate with the Presidential family, was philosophical in the extreme — for, pulling from his pocket a meerschaum, colored as only college boys can color pipes, he proceeded, with the stoicism of an aboriginal Indian, the pertinacity of a Scotch creditor, and the success of a Yankee fisherman, to puff, puff, puff, until enclouded in the savoring vapor, he was lost to view. The paternal LINCOLN, to be sure, said nothing: but these is little doubt that he felt hungry all the more: the various Colonels, Generals, Captains and Honorables walked up and down, up and down, the Committeemen blushed, explained, apologized and felt very warm, while the correspondents aforesaid rolled themselves up in their overcoats and shawls, and in sweet sleep, lost all conciousness of trouble, and dreamed only of the dinner yet to come. …

The reception at Columbus was worthy of the occasion…

[At the state capitol] Lieutenant-Governor KIRK had the honor of welcoming Mr. LINCOLN, and may congratulate himself upon having drawn from the lips of the wary Illinoisian, a speech which, for kindly sentiment, and for cheering import, has not been equaled in many a day, and which, ere this, sent as it bas been, by the lightning wire, into all parts of the country, has gladdened the hearts of patriots, and set at rest the fears of statesmen. After the speech, he went upon the left extreme of the western steps, from which point he commanded a clear view of the largest and finest appearing assemblage he has seen during his present tour. He unanimous was the greeting, and so enthusiastic the shouting, that for a moment the inner man triumphed, and Mr. LINCOLN was visibly moved to tears. He again addressed the crowd, and though his speech was short, it was telling and to the point, so that at every sentence, cheer after cheer rent the very air.

The same assemblage undaunted by the mud upon the streets, followed the carriage which conveyed him to the Governor’s private residence, where with the family of Mr. DENNISON and his immediate circle, Mr. LINCOLN dined and subsequently rested prior to the ovation of the evening.

At eight this evening a tide of joyous people from all neighborhoods hereabouts flowed toward the gubernatorial mansion. Invitations were liberally extended, and with pleasure accepted — so that, accustomed as the hospitable Governor is to a crowded house, he must have been astonished at the thronging multitude which took possession of his home to-night. …

You can read the entire article at The New York Times Archive

Lincoln is starting to show his “deep-set furrows and wrinkles” during the ordeal just getting to Washington. The rabid and ravenous crowd in Xenia devour his lunch. And yet a tear comes to his eye when he sees the immense throng in Columbus.

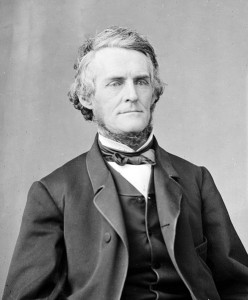

William Dennison, Jr. refused to comply with the Fugitive Slave Act during the time he was governor. He served as Postmaster General from 1864-1866.

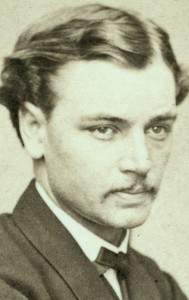

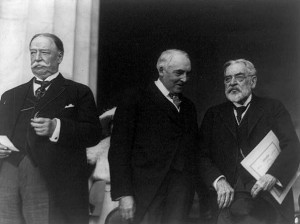

As you can see Robert Todd Lincoln (1843-1926) attended the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922.