As the Daily News sites have noted the Charleston Mercury has been beating the drum for South Carolina’s secession, especially since Lincoln’s election.

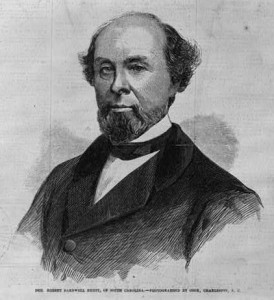

The Mercury was edited by Robert Barnwell Rhett, Jr., whose father was a well-known fire-eater. Robert Barnwell Rhett, Sr. resigned from the U.S. Senate in 1852 but continued to push his strongly pro-secessionist beliefs through the Mercury.

Here The New-York Times editorializes on the Mercury’s continuing push for secession (December 6, 1860):

– The Charleston Mercury is becoming alarmed at the indications of delay in the secession movement. It is especially, afraid of the proposition to postpone action until Virginia and the other Southern States can be consulted. The refusal of the Old Dominion to meet South Carolina in conference, after the JOHN BROWN affair, is reproachfully called to mind, and her motive in now seeking such a conference is denounced as selfish and base:

“Virginia declined counseling with us,” says the Mercury, “because her views of her interests differed from ours. She set up an alienation and separation from us, against our most earnest remonstrances and efforts; and if she now seeks to be heard by us, what is her object? Is it to aid us in our views of policy –to preserve our rights or save our institutions? Not at all. It is to defeat our policy by a Southern Convention, and to drag us along in subserviency to her views of her border interests. If we respectfully decline to delay in our course, that she ‘may be heard,’ we only treat her, as she has previously treated us.”

The Mercury has no idea of being “dragged along” by what the Southern States may consider to be their common interest. It proposes that South Carolina shall plunge in alone, and then drag down all the other States by insisting on their coming to her rescue. This is the high-toned, magnanimous policy of the Palmetto State.

The Mercury proceeds to consider other reasons that are urged for delay, — first among them the prospect that the Northern States may repeal their Personal Liberty bills. And on this point the Mercury makes the following very frank admissions:

“So far as the Cotton States are concerned, these laws, excepting in the insult they convey to the South, and the faithlessness they indicate in the North, are not of the slightest consequence. Few or none of our slaves are lost, by being carried away and protected from recapture in the Northern States. Nor to the frontier States are they of much consequence. Their slaves are stolen and carried off — not by the agency of these Personal Liberty laws — but by the combination of individuals in the Northern States.”

This confirms what we have repeatedly urged, — that the clamor about these Personal Liberty bills is to a very great extent hollow and unmeaning. Unquestionably they afford a pretext for a good deal of the denunciation of the North which is so popular in the South just now, — and their repeal would strengthen the Union Party in that section. But they do not constitute the real motive for disunion anywhere.

From what I’ve read I am not sure that Southerners don’t care about the Personal Liberty laws. However, I can see how Rhett and the newspaper would not want anything to slow down the momentum building in South Carolina for secession – not the interests of the other southern states, not any possible repeal of the Personal Liberty laws.

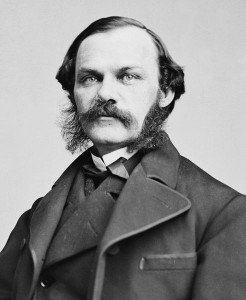

The Times editorial was not attributed to anyone; however, Henry Jarvis Raymond was a founder of The New-York Times and was its editor until he died.

Raymond was New York State’s Lieutenant Governor in 1855 and 1856 and was involved with Republican Party politics. In October and November of 1860 Raymond carried on a public exchange of letters with another fire-eater – William Yancey. You can read Raymond’s response to Yancey’s letter at The New-York Times Archive. It seems that Rhett and Raymond have at least something in common – they are both highly political and use the press to express their views. Of course, they’re diametrically opposed on issues like slavery and secession.