Lincoln’s Reaction to His Election

As other Civil War sites have noted, there was the expected strong and negative reaction to Lincoln’s victory throughout the South. On November 8, 1860, The New-York Times. published a report from the President-elect’s home about how Lincoln spent the last couple days and to see if he had any words about future plans for his administration. Here are some excerpts:

Special Dispatch to the New-York Times.

SPRINGFIELD, Ill., Wednesday, Nov. 7—6 P.M.

Mr. LINCOLN has not yet given any public intimation as to the policy of his Administration. I have every reason to believe that he will not depart from the usual custom of newly-elected Presidents. In answer to all inquiries as to what will be his course, he asks, “Have you read my speeches?” If the question is still pressed, he quietly hands over one of the pamphlet publications of his speeches in the late controversy with Mr. DOUGLAS. …

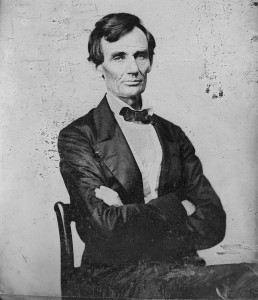

That Mr. LINCOLN is a man of sufficient ability and nerve to meet any exigency, is conceded by all who know him. I believe, from what I see of him here, that he will prove a second JACKSON— only more so. When he thinks proper to make a pronunciamiento, you may depend upon it he will do so. …

Mr. LINCOLN spent most of election-night in the Telegraph-office, where he heard returns and received private dispatches with a most marvelous equanimity. Those who saw him at the time say

it would have been impossible for a bystander to tell that that tall, lean, wiry, good-natured, easy-going gentleman, so anxiously inquiring about the success of the local candidates, was the choice of the

people to fill the most important office in the nation. Even during election day and night, Mr. LINCOLN was about town attending to his business as usual. Many of his Springfield acquaintances will long remember how he sat in a social circle at the Cheny House while the returns were coming in, and indulged alike in pleasant chat and his propensity for story-telling.

SPRINGFIELD, Ill., Wednesday, Nov. 7—P. M.

Mr. LINCOLN was this evening captured by a number of his friends who carried him to the Hall of the House of Representatives, where about three hundred citizens spontaneously collected and earnestly but vainly pressed him for a speech. They finally got him in the Speaker’ s chair …

Mr. LINCOLN finally, in a jocular way, took advantage of his position as Chairman, to say that it was customary for the presiding officer to call

some distinguished member to the Chair . He accordingly called Mr.KENT to take his place, and retired through a side door, in spite of vociferous calls for him to speak. O., JR .

So Mr. Lincoln exits stage left (or right). Thankfully he showed up in Washington the next March for his inauguration. For a good overview of why the four months between Lincoln’s election and his inauguration were dicey for the country check out The American Civil War and its article about the disunion sentiment in the Buchanan administration.

The word that sticks out for me in The Times report is equanimity. While people in the South were clamoring for war and some Northerners were proclaiming the Union saved (see “Raising the Red Flag” in Civil War Daily Gazette) Lincoln was quietly handing out his speeches to show his intentions. That also showed that Lincoln would live up to his words.

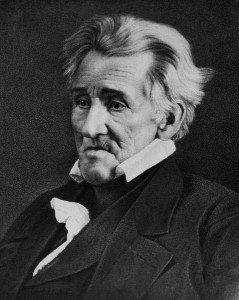

I was a bit surprised when The Times correspondent likened him to Jackson because I don’t think that Jackson was known for his equanimity. But I know the correspondent was talking about Lincoln being strong and decisive and speaking when it was necessary, in his opinion, for the good of the nation.

Can you imagine a victorious politician nowadays refusing to give the media a nice juicy soundbite? Instead, “here’s my speech from two years ago.” By the way, The Times did excerpt some of Lincoln’s speeches in the same November 8th issue.

I think that the comparison to Jackson probably refers to Jackson’s response to the nullification crisis of 1832, when South Carolina refused to abide by a compromise tariff bill. The protective tariff was generally seen to aid the industrial North while raising the prices of imported manufactures in the agrarian South. Congress passed a “force bill” in 1833 authorizing the president to put down nullification with military action. As I’ve noted elsewhere, many Northerners looked for Lincoln to emulate Jackson’s strong stand if Southern states threatened secession.

Thank you for the insight, Allen

When I posted this yesterday I thought that Lincoln’s reticence was probably a good thing given how fired up the secessionists were. He had only been president-elect for a day. The Buchanan administration would be in power for another four months. He probably wanted to get his cabinet setup and think things through.

Yesterday afternoon at our public library I read an editorial from a local paper from early January, 1861. From what I’ve read so far it seems this was a Democrat-leaning newspaper. The article was very critical of the Republicans. One of the things it did not like was that there had been no statements of policy intentions from Lincoln.

It seems like the four month lag between election and inauguration was becoming an issue, especially given the telegraph and railroad systems.