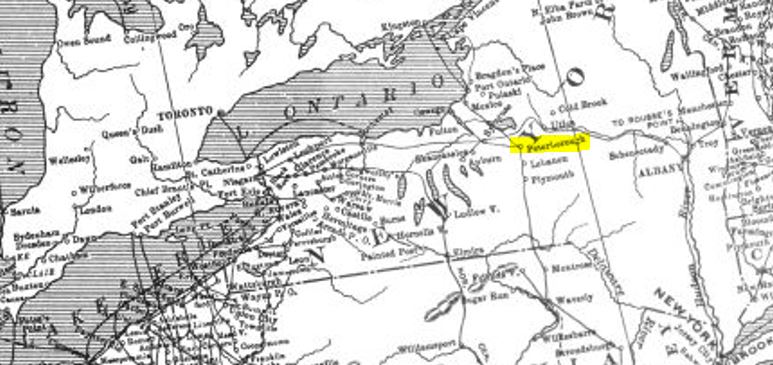

150 years ago May 30th fell on a Sunday, so it appears that many communities observed Memorial Day on either the 29th or the 30th. According to an editorial from Portland, Maine, many people were surprised that ten years after the end of the Civil War the Decoration Day was still being The paper thought it was right to honor those who died “while battling for human freedom and popular government” and wondered if the tradition would continue after every Civil War veteran had died. The editorial went on to say that it was good that the sections were reconciling, but it wasn’t right to honor Confederates dead in the same way as the deceased Union military personnel.

From the May 31, 1875 issue of the Portland Daily Press (in Maine):

Memorial Day.

It has been predicted by many that Memorial day would be observed but a few years; and there certainly was reason to fear that the intense zeal of our people to secure the greatest amount of present good, the past with its labors and sacrifices would to be forgotten. But those who have made such predictions or entertained such fears, are doubtless surprised to observe that the days set apart for memorial services of the nation’s dead this year, are more generally observed than at any previous time, proving that the American people are not unmindful of or ungrateful to the memory of the patriot dead. In view of the general purpose of the people to render tribute to their fallen defenders, may we not expect that when the last veteran of the late war has been added to the roll of the dead, the succeeding generations which reap the blessings secured by their devotion and valor, wilt hallow Memorial Day?

It should be so; for no generations or nation can monopolize the fame or the achievements of those whom we honor to-day, nor is their patriotism or devotion exclusively the product of the age in which we live. The men whom we honor to-day have fallen in one of the battles in that century-long conflict between freedom and oppression. That same immortality which pours its golden light down through the vista of centuries upon the defenders of Thermopylae, is theirs. Names are lost; faces are forgotten; time and space are annihilated; deeds alone live; so that by that kinship which unites heroic purpose and self-denying devotion in all ages, the souls who tasted immortality at Thermopylae, the martyrs who died in hopeless conflict with the brutal tyranny of the feudal ages, the men who crimsoned the slope of Bunker Hill or at Valley Forge, displayed such fortitude and endurance, and the men who fell by thousands for freedom in our late war — all these martyrs have fought under one banner, and their deeds, their victories and their examples are our priceless heritage.

How fitting are these reflections on these memorial days, when it is remembered that under the green mounds upon which are placed the floral offerings, lie stranger forms, who, as men, would be no more to us than others, but resting from life’s battle in graves hallowed by martyrs’ deaths, the memory of their deeds makes them our dead, as is the country they saved our heritage. To-day we would not recognize the faces of many of those we honor. Their voices would awaken no chord of memory. Many wanderers, many from beyond the sea, many whose tongues had not learned our speech, many to whom our flag was the emblem of deliverance, are among them; but lying there we know them all, and the benediction of the Republic falls like rain upon them, and when the first waves of vendure break in spring flowers upon our Northern hill – sides, we gratefully gather them for our annual offering to them.

We know there are many whose extreme devotion to the practical leads them to look with little favor upon Memorial Day and its exercises. They ask: Of what good, not to the dead, how to the living? It is useful, Mr. Gradgrind, to save the nation from your sordid mold. We need to pause once in a while to think of something else than the mad pursuit of wealth and to step out of the round of every -day work, which makes us little better than machines. We need to recall the past with its great deeds. We need to pay the memory of heroic men the reverence there [sic] due and thereby call down upon ourselves the inspiration of their devotion and the fragrance of their memories. We must not forget that into that sublime half decade of war was profusely pored the highest hopes, the grandest ambitions, the most exalted sacrifices and the most precious life of the nation. It is, indeed, a sad day for the nation, if it has come to pass that the generation which laid life and temporal prosperity upon the country’s altar, has come to place a slight value upon that high devotion which led it to brave death for principle. Dark, indeed, to-day, if before the arms are rusted or the old uniforms moth-eaten, the American people should forget to hallow these days. We must not forget that upon our dead in the war, the blood-stained mantle of freedom was consigned by the fathers. Dying while battling for human freedom and popular government, they have transmitted that heritage, richer by their lives and costlier by their deaths.

To-day, as we stand amidst the graves of the nation’s saviors, we thank God that the jealousies and heart-burnings of the war are dying out — that manly forgiveness and brotherly love are succeeding. Standing above our dead, the man who wore the blue offers his hand to the man who wore the gray. Tears glisten a reconciliation which quivering lips cannot speak. Their clasped hand is a token of the Union which is to be.

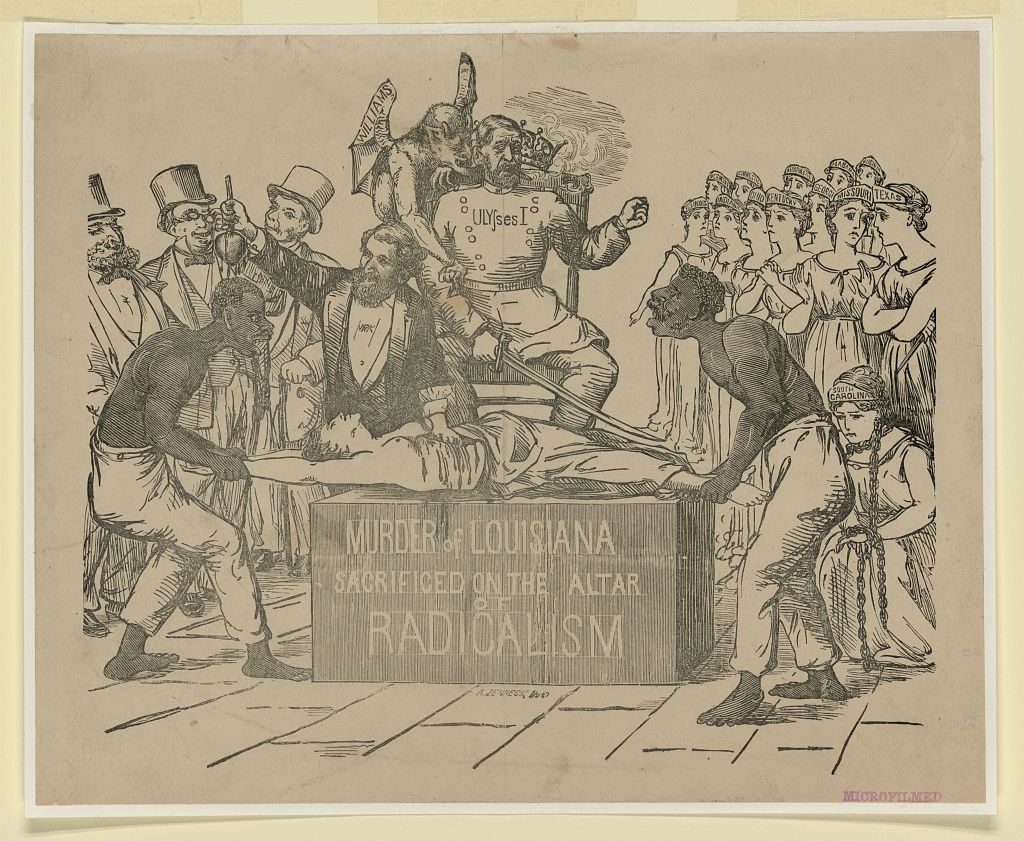

But while we have tears, pity and kindness for the gray, we should reserve our garlands and honors for the blue. There are many who would go further — who would put the man who died fighting against national existence on a level with him who poured out his life to preserve it. We do not desire to have treason punished, but we do protest against making that crime a virtue to be rewarded alike with loyalty. Neither do we think this course is necessary to show our good will to our Southern brethren. Hundreds of occasions present themselves to show our friendliness. The summer pestilence of 1873 and the Mississippi floods of 1874 were occasions for us to show our brotherly regard, and right generously did the North respond. The Christian world had as well be asked to show its conciliation toward those who crucified the Lord by paying the same homage to those who put Him to death as to the Master himself. When we put the men who died in defense of Right on a level with those who died to perpetuate Wrong, we strike their names from the roll of the world’s martyrs. Let us rather cherish our dead because they were a nation’s redeemers; because in the thick night, with strong faith, with godlike devotion, with blood-stained colors, they wrought the salvation of fatherland.

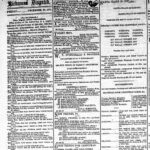

Here are some clippings from the same issue of the newspaper. Washington D.C. observed the holiday on May 29th. President Grant and cabinet members attended the memorial service at Arlington National Cemetery. Citizens also went fishing had picnics, and enjoyed steamboat excursions on the Potomac. The Southern Memorial Association would decorate Confederate graves on the next Tuesday. The GAR decorated graves in Portland on May 31st, and P.T. Barnum’s Hippodrome was in town for three performances on the “The Nation’s Saddest Holiday.”

__________

The Fayetteville, Arkansas chapter of the Southern Memorial Association is still in operation: “The next Southern Memorial Day Ceremony will be held on Saturday June 7, 2025 at 10:00 a.m. at the Confederate Cemetery.” The site’s history page echoes the Portland editorial: “When another hundred years have passed, will the Confederate Cemetery on East Mountain still stand as a tangible reminder of the brave men who died for a way of life they held dear and the proud women who loved and honored them?”

![Merry Christmas (New York : Published by Currier & Ives, 125 Nassau St., [1876])](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/09454v.jpg)