After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated his body was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois. 150 years ago today a large monument at the Lincoln grave site was dedicated. In its October 24, 1874 issue Harper’s Weekly described the monument:

THE LINCOIN MONUMENT

AT SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS.

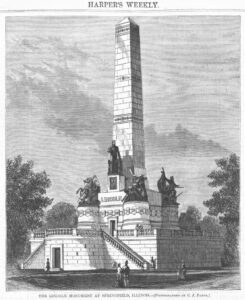

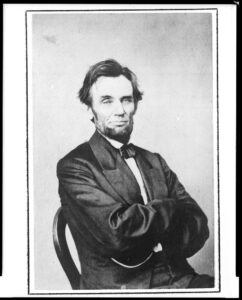

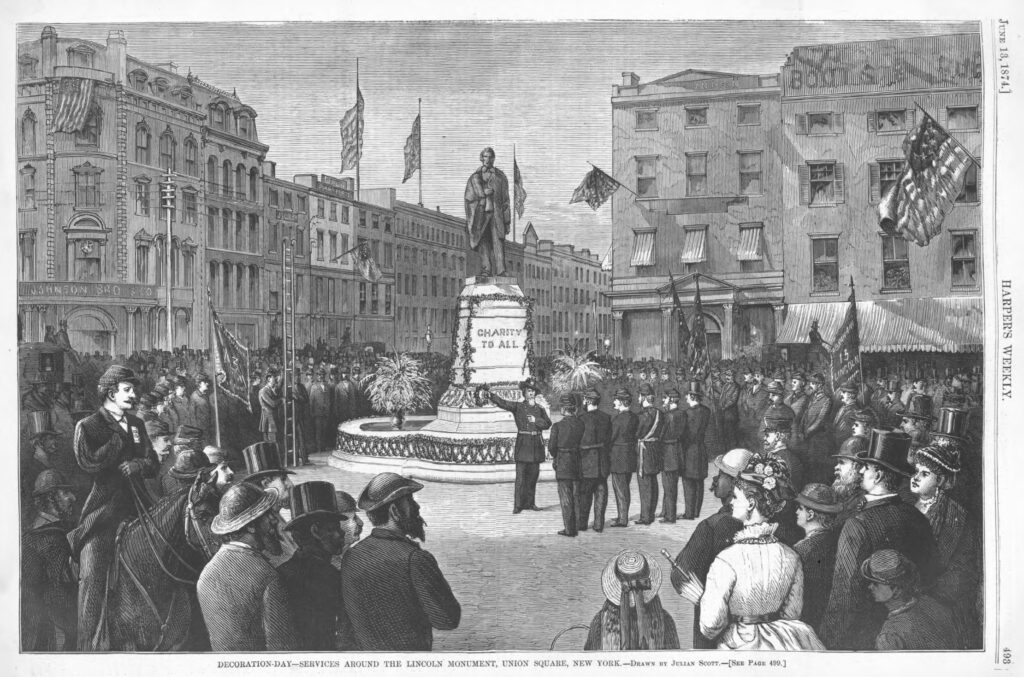

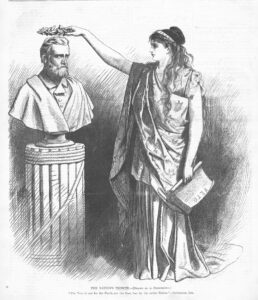

WE give on this page an illustration of the monument erected at Springfield, Illinois, in honor of President LINCOLN, which includes a bronze statue of the President modeled by Mr. LARKIN G. MEAD. The statue was put in its place on the 3d inst., and was formally unveiled on the 15th in the presence of a vast assemblage of people from all parts of the country. It stands on the south side and in front of the shaft, about thirty feet above the ground. President GRANT and many other distinguished guests, both civil and military, were present at the ceremony. The statue is an excellent and characteristic likeness of Mr. LINCOLN. The figure is represented as dressed in the double-breasted long frock-coat and the loose pantaloons which were the fashion ten or twelve years ago, and consequently make the form appear somewhat more full and robust than Mr. LINCOLN really was. The portraiture of the statue is realistic in its fidelity. The rather stooping shoulders, the forward inclination of the head, manner of wearing the hair, the protruding eyebrows, the nose, the mouth, with the prominent and slightly drooping lower lip, the mole on his left cheek, the eyes sitting far back in his head, the calm, earnest, half-sorrowful expression of the face, all recall to the minds of his old friends and neighbors the simple-mannered, unaffected man who lived among them until he was called away to enter upon the duties of Chief Magistrate of the nation.

As will be seen from our engraving, Mr. LINCOLN is represented with his left hand resting upon fasces, around which are gracefully folded the Stars and Stripes. Mr. LINCOLN is represented as having just signed the Proclamation of Emancipation, and in his left hand he holds a scroll marked “Proclamation;” in the right hand he holds a pen. The coat of arms upon the face of the pedestal on which the statue stands represents the American eagle standing upon a shield partly draped by the flag, with one foot upon a broken shackle, and in his beak the fragments of a chain which he has just broken to pieces.

The monument is constructed in the most substantial manner of Quincy granite. In the base are two chambers. The one shown in our engraving is called Memorial Hall, and contains some interesting relics of the late President. The other, on the north side, contains the caskets inclosing the remains of Mr. LINCOLN and his little son “Tad.” The opening above Memorial Hall is the entrance to the winding stairs leading to the top of the monument. The several subordinate groups of figures shown in our engraving are not yet placed in position. Each group is intended to represent a branch of the service of the United States.

The monument was erected under the superintendence of Mr. W.D. RICHARDSON, from the design of Mr. LARKIN G. MEAD. The base is seventy-four feet on each side and twenty high, the total height to the top of the shaft being one hundred and twenty feet. The structure cost $250,000.

In its October 16, 1874 issue The Chicago Daily Tribune covered the dedication ceremony. It was a major event with thousands in attendance. Even the generally quiet Ulysses S. Grant spoke a few prepared words. From page 2 of the newspaper:

SPEECH OF GEN. GRANT.

Gen. Grant was loudly called for and read the following address:

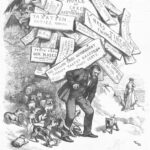

MR. CHAIRMAN, LADIES, AND GENTLEMEN: On an occasion like the present, I feel it a duty on my part to bear testimony to the great and good qualities of the patriotic man whose earthly remains now rest beneath this dedicated monument. It was not my fortune to make the acquaintance of Mr. Lincoln until the beginning of the last year of the great struggle for national existence. During those years of doubting and despondency among the many patriotic men of the country, Abraham Lincoln never for a moment doubted but that the final result would be in favor of peace, union, and freedom to every race in this broad land. His faith in an all-wide Providence directing our arms in this final result was the faith of the Christian that his Redeemer liveth. Amidst obloquy, personal abuse, and hate undisguised, and which was given vent to without restraint through the press, upon the stump, and in private circles, he remained the same staunch, unyielding servant of the people, never exhibiting a revengeful feeling towards his traducers, but he rather pitied them, and hoped, for their own sake and the good name of their posterity, that they might desist. For a single moment it did not occur to him that the man Lincoln was being assailed, but that a treasonable spirit, one willing to destroy the freest Government the sun ever shone upon, was giving vent to itself upon him as the Chief Executive of the nation, only because he was such Executive. As a lawyer in your midst, he would have avoided all this slander, for his life was a pure and simple one, and no doubt he would have been a much happier man; but who can tell what might have been the fate of the nation but for the pure, unselfish, and wise administration of a Lincoln? From March, 1864, to the day when the hand of an assassin opened a grave for Mr. Lincoln, then President of the United States, my personal relations with him were as close and intimate as the nature of our respective duties would permit. To know him personally was to love and respect him for his great qualities of heart and head, and for his patience and patriotism. With all his disappointments from failures on the part of those to whom he had intrusted command, and treachery on the part of those who had gained his confidence but to betray it, I never heard him utter a complaint, nor cast a censure for bad conduct or bad faith. It was his nature to find excuses for his adversaries. In his death, the nation lost its greatest hero. In his death, the South lost its most just friend.

The Daily Tribune report included several notes from famous people who regretted not being able to attend the monument dedication. Many of these fought in the Civil War. For example, James Longstreet wrote from New Orleans, and Ambrose Burnside wrote from Chicago on October 14th – he was actually on his way to the ceremony when he found out he had to head back East right away.

__________